Edvard Munch’s Own Publications

Among the texts and writings that Edvard Munch had published himself throughout his life, there are few literary works, even though many of the unpublished literary notes were probably intended for publication in one form or another. In periods he moved in literary circles; among poets, novelists, journalists and writers, and this was probably very important for his perception of his own writing and publishing endeavours. Most of the published texts span a number of genres and many were written out of necessity and printed in different newspapers, magazines, exhibition catalogues and other publications; commentaries, letters to the editor, contributions to debates and responses to criticism. And obituaries. There are also scattered texts of a more quaint nature, which resemble the humoresque and causerie genres; and even an advertisement text and a political commentary. Munch also wrote a number of similar texts and articles that he never sent off, and still others that he submitted for publication, but which were not printed. He likewise worked on illustration commissions that never materialised. Some of these are interesting within the context of this article in the sense that they can contribute to a more complete picture of his movements, strategies and desire to make his mark in the public eye.

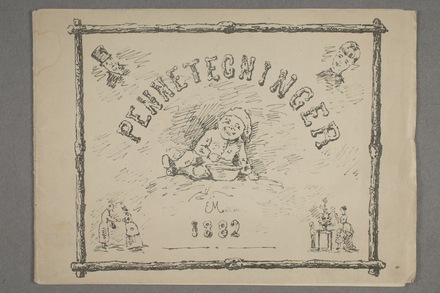

ILL. 28. EDVARD MUNCH: PEN DRAWINGS 1882. COVER AND COMICAL DRAWING. The Teacher: What does it mean to be in the Power of the Devil, Peter? — Peter keeps silent — The Teacher (gripping his Shoulder) In whose Power are you now? — Peter (frightened) In – in ... the Devil’s!

Early Publications

Munch was conscious of a desire to have his own works made public early in life. In 1877 the non-profit magazine For Ungdommen announced a drawing contest, and he sent in two drawings. The competitive aspect was most likely important for the 14-year-old, but to have a drawing printed in a magazine would have been seen both as an honour and as a significant form of recognition. But the competition – unfortunately for the young Munch – never materialised and was forgotten by the editors.

In 1882 he made a lithograph of some comical drawings and had it published as a booklet at his own expense (ill. 28). The artist’s sister Inger Munch noted down the following on the only impression in the Munch Museum: “An attempt at making a little money. Disappointment.” Many years later, in 1910, his friend and relative Ludvig Ravensberg mentioned the booklet in a conversation with Munch: “I remind Edvard of his comical drawings, and he says o dear, I blush when I think of them. Oh they are not such bad drawings I say, but the jokes are poor. He laughs with his insane laughter [...] Yes, there is something between these and Alpha and Omega. The letters in particular fill me with horror.”1 The booklet was also mentioned in the newspaper: “Yes, I say, I remember witty drawings by E.M. in the newspaper a bit original and funny.”2 Throughout the 1880s he also drew – perhaps with the hope of publishing – a number of drawings that had the traits of caricatures, and others that were purely descriptive drawings.

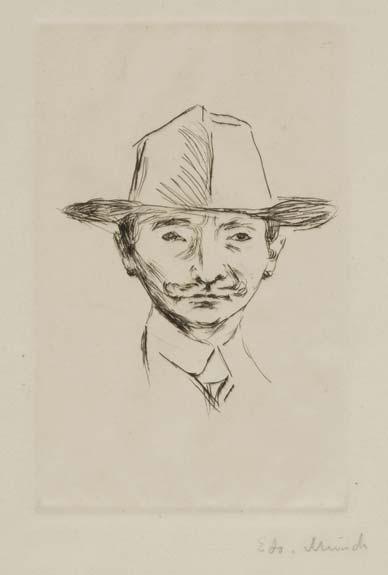

CAT. 28. HELGE RODE 1908

Edvard Munch became acquainted with literary personalities early on. At the artist carnival in March 1886 he met the notorious writer Hans Jæger. He met other writers at this time as well, Herman Colditz, for example, who in 1888 published his roman à clef novel Kjærka (The Church). Munch himself is depicted in it, in the character of the painter Nansen, a pseudonym he would later use in his own literary notes. At this time he was also interested in reading authors who were discussed at the time, both Hans Jæger and Henrik Ibsen and other naturalists, but also Dostoyevsky, whose major works were translated into Norwegian during the 1880s. Several other writers eventually joined Munch’s circle of acquaintances. During his first lengthy study tour to Paris he met the Danish poet Emanuel Goldstein in a café or bar, some time in the late autumn of 1889. After Munch learned of his father’s death in November he moved, immediately after the New Year, away from the intense Norwegian milieu in Paris to the suburb of St. Cloud, where Goldstein was also staying. Many Munch scholars – and also Munch himself, later in life – have pointed to Hans Jæger as a model for Munch, both as a painter and as a writer. But it is most likely that the company of Goldstein in St. Cloud was just as important a catalyst for his taking up writing. It was here that Munch also somewhat hesitantly noted down an artistic credo, woven into an account of a popular cabaret with a confusion of people, cigarette smoke, female dancers and music. The notes have later been called the St. Cloud Manifesto,3 and as we shall see, he returned to this text in a publication of his own later in life.

Literature, Visibility and Fame

In the fall of 1890 Edvard Munch left again for France in order to continue his studies. He travelled by boat to Le Havre where he remained bedridden in a hospital for two months due to an attack of rheumatic fever before continuing his trip. It may have been here that he bought the notebook, which at the Munch Museum has traditionally been called The Violet Journal. In January of 1891, for reasons of health, Munch passed quickly through Paris en route to Nice. Deeply moved by the beauty of the city, the soft Mediterranean light and the mild climate with the bustling street life, he wrote diligently in his journal: impressionistic episodes from the promenade along the shore, small sketches from cafés and restaurants, and descriptions of the boisterous and gay carnival. A few written drafts from here formed the basis for Munch’s first publication. In a letter to Karl Vilhelm Hammer, journalist in Verdens Gang and possibly an acquaintance from his time spent in the company of the Kristiania Bohemia, Munch requested to have the newspaper forwarded to Nice. In the letter he enclosed a few of his journal notes, in the hope that they could be of use: “If you can you use some of these enclosed outpourings you are welcome to do so – rearrange them as You wish”.4 And on 11 February 1891 Munch had his first text printed in the form of a little travel account – with clear literary qualities – in Verdens Gang under the title “Queen of the Mediterranean. Letter to ‘Verdens Gang’”.5 When the English composer Frederick Delius held a concert in Kristiania in October 1891, Munch – most likely at the suggestion of Hammer – had a portrait of the composer, based on a previously made drawing, printed along with a review of the concert in Verdens Gang.6

CAT. 74. EMANUEL GOLDSTEIN 1906

In the summer of 1891 Munch was awarded the Government Grant for artists for the third year in a row, and when he left for France and Nice later in the fall, Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson complained indignantly in Dagbladet over the fact that the grant in Munch’s case was being used as a sick pay fund to pay for a health spa in Nice. Munch defended himself quite tersely a few weeks later in the same newspaper in the article “To Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson”.7

On 22 January 1892, Edvard Munch penned – somewhat tentatively – the first prose poem that was linked to the Scream motif in his notebook. He was living on the outskirts of Nice, at this point, together with the painter Christian Skredsvig and his wife Maggi. Munch had probably visited Emanuel Goldstein on his way to Nice and throughout the spring of 1892 they continued their many discussions in a copious exchange of letters; letters that primarily had to do with art, literature and an illustrated vignette that Goldstein wanted Munch to draw for his upcoming collection of poems, Alruner. The vignette, in the form of a little drawing based on the Melancholy motif, was delivered – after many reminders from Goldstein – and printed in the book that was published the following year. In addition to the collection of poems, Goldstein had plans to publish a little book of aphorisms on art theory that he called Kammeratkunst (Comrade Art) and spoke of it in several of the letters, and even sent the introduction to Munch for commentary. The introduction was published in the literary daily København (Copenhagen), but the book was never published. Goldstein also encouraged Munch to publish in København: “I have spoken with Ove Rode about whether he would like to have some letters from Nice, and he would very much like to.” Munch had most likely proudly shown Goldstein the travel account in Verdens Gang and perhaps allowed him to read related texts from the notebook; such as the description of the carnival and scenes from the casino in Monte Carlo. These new travel accounts never amounted to anything, however. Goldstein and Munch had also for a long time been planning to start a new literary journal where they could both publish – for Munch’s part, presumably some of the literary notes he had been working on in St. Cloud: “And all of these perfectly good realistic drafts we both made at that time in Paris – all of the phonographic representations of scenes – that were so well thought out – shall they ever be used – You have a pretty large pile of them too”.8 The plans for a literary journal were perhaps a pipe dream for both of them and were soon forgotten. It appears that they both – Munch in particular – became tired of both philosophising and writing. This remark from the summer of 1892 seems to have marked the end of the intense work with the numerous autobiographical literary notes that began in 1889: “I am beginning to get a bit tired of all these people who write about their lives – One walks around in constant fear of being dragged up to the seventh floor to be presented with a life spanning 2000 pages – there is hardly a man here who has not written the novel of his life”.9

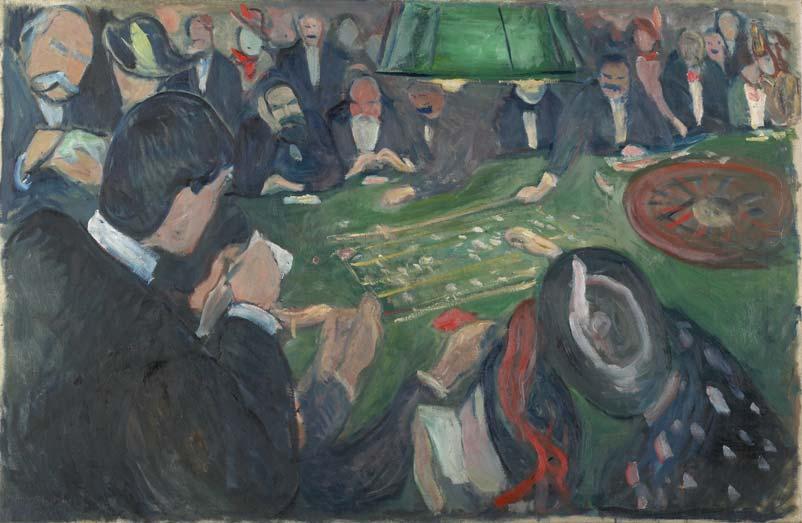

CAT. 6. BY THE ROULETTE IN MONTE CARLO 1892

During this period Munch had contact with several other authors and writers, among them the poets Vilhelm Krag and Sigbjørn Obstfelder who also wanted Munch to illustrate their respective first collections, but nothing came of the vignettes. It appears that he may have had problems tearing himself away from his own imagery when he tried to illustrate the writings of others. Krag included the poem “Night. Painting by Edvard Munch” in his first collection of poems, however, which was published in December 1891, and the following year, in connection with Munch’s extensive solo exhibition in September, Vilhelm Krag published a poem in Dagbladet inspired by Munch’s painting Sick Mood at Sunset. Despair.10 Krag had undoubtedly read or heard read out loud Munch’s prose poem that was associated with the Scream motif. Although Krag’s poem was stricter in form and partly in rhyme, the imagery and certain formulations are strikingly similar. Munch would not forget his own text related to Scream so easily, however.

Upon invitation, in November 1892 he exhibited a large number of works at Verein Berliner Künstler’s premises in Berlin. After the public’s and the critics’ shocked encounter with the pictures, and the controversies within the art association that followed in its wake, the exhibition was closed down after a week and a scandal was unavoidable. Munch became both infamous and famous overnight, and the Kristiania newspapers immediately wrote about the scandalous exhibition. In a letter to K.V. Hammer, Munch writes that he wishes to comment on the case himself in the press: “I would like to have the enclosed article in Verdens Gang as soon as possible, and then I will send You an article in which I will give You an idea of the situation that my exhibition has created down here – I do not expect that the papers will do more than take in the poor reviews of my exhibition – I am very satisfied with the situation by the way [...]”.11 The articles were, surprisingly, never published.

Scream

Munch moved in literary circles in Berlin, among authors such as Stanislaw Przybyszewski, Ola Hansson, Holger Drachmann and August Strindberg. When he moved to Paris around the middle of the 1890s he continued to meet Strindberg, who was also living in the city. Munch had painted Scream in Berlin in 1893, and in 1895 he had a lithographic version of the motif printed.

The editor of the French literary journal La Revue Blanche, Thadée Natanson, travelled to Kristiania in 1895 to meet Henrik Ibsen, but he also met Edvard Munch and visited his exhibition at Blomqvist. It was slaughtered by the press, but was praised by Ibsen himself, whom Munch had given a tour of the exhibition. From Kristiania Natanson sent a report, a Correspondance, which was printed in La Revue Blanche on 15 November 1895. This report also contained – aside from a presentation of the young playwright Gunnar Heiberg penned by none other than K.V. Hammer – Natanson’s review of Munch’s exhibition. The article was illustrated with a drawing based on the lithograph of Scream, and Munch’s prose poem in a French translation:12 “The text that comments on the picture is one of the small poems that Monsieur Munch has the habit of supplementing his compositions with. The document thus confirms the Norwegian painter’s literary interests.”13 Munch had honed the original text from 1892, and attempted rather helplessly to translate it into French himself.14 He was probably aided by a friend skilled in French; perhaps Jappe Nilssen or Sigurd Høst. He had originally added the Norwegian text to a section of the frame on the pastel of Scream which he had made the same year. The New York based magazine Mademoiselle15 published a response to the article in La Revue Blanche in January 1896 with a reproduction of the lithograph of Scream and Munch’s prose poem in English translation. In 1897, Stanislaw Przybyszewski reproduced the illustration and the poem in an article about Munch in the Czech journal Moderni Revue. The foundation for not only the Scream motif, but also the prose poem’s eventual iconic status was, as one can see, laid very early.

Poem and Illustration – Play and Narrative

When Edvard Munch in 1896 exhibited at the Salon de l’Art Nouveau in Paris, August Strindberg reviewed the exhibition in La Revue Blanche. A major part of the review was formed as a series of concise prose poems devoted to some of the motifs, perhaps influenced by Munch’s own prose poem in Natanson’s review. Munch and Strindberg collaborated in 1898 on a mutual publication in the journal Quickborn. The entire issue was devoted to Strindberg’s texts and Munch’s pictures in an open artistic dialogue. At the same time Munch was working on illustrations for Charles Baudelaire’s Les fleurs du mal, in the form of vignettes that would practically frame the poems. There is a similar vignette of the Vision motif in the Munch Museum with Munch’s own prose poem devoted to the motif, meticulously and beautifully written by hand in the caption. It is possible that he played with the idea of likewise printing a selection of his handwritten prose poems, framed by his own illustrations. The placing together of images and text are reminiscent of William Blake’s etchings of his own illustrated poems, which Gösta Svenæus has pointed out in connection with Munch’s compositions for Les Fleurs du Mal.16 The illustrations for Baudelaire’s cycle of poems was never printed.

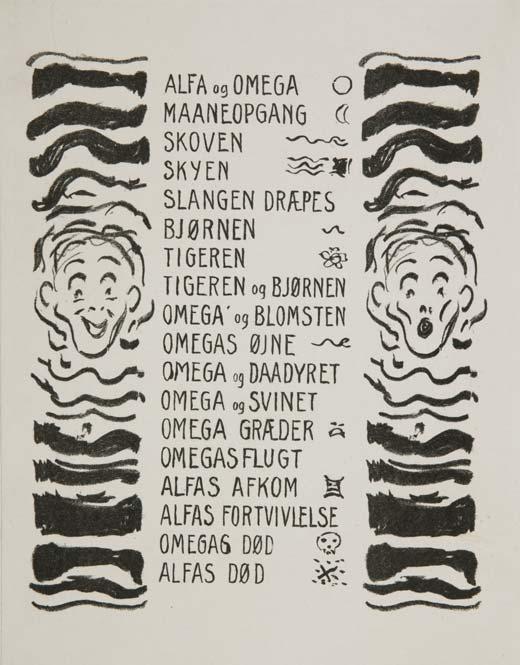

CAT. 75. ALPHA AND OMEGA. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1908–09

Many of Munch’s literary notes from around 1900 and later changed character in the direction of greater visual richness, and in the direction of satire and caricature. In 1905 he worked on a little play, “a full-scale comedy called The City of Free Love”,17 which was intended as a settling of accounts with the aging Bohemian milieu in Kristiania and its old ideal regarding free love. Well satisfied with the manuscript, Munch asked Ludvig Ravensberg half jokingly to put a little ad in Verdens Gang, “The Enemy’s [Bohemia’s] Newspaper”: “Edvard Munch has aside from painting also busied himself with Literature – He has already completed a Comedy [...] I think this little Article will tickle these People somewhat.”18 Neither the ad nor the comedy about free love was printed. Munch would continue to develop the theme, however, in the little story or fable Alpha og Omega about “the first humans”, which accompanied the cycle of pictures he drew and had lithographs made of in 1908, and which were collected in an exclusive portfolio (cat. 75). The text was included in the portfolio in Norwegian and in French translation,19 and during subsequent years was printed in several exhibition catalogues as a supplementary and illustrative narrative to accompany the series of pictures that was exhibited on the gallery walls – in Norwegian and in French or German translation.20

Scattered Articles

Between 1910 and 1930 Edvard Munch published a number of different types of articles and commentaries. And on various occasions the self-appointed recluse at Ekely behaved coquettishly and jovially during several rather meaningless interviews. In the catalogue for the exhibition of the competition sketches for the Aula decorations at the Diorama premises in 1911 he wrote a brief and succinct statement regarding the composition and idea behind the decorations. At about the same time he wrote – in anger and irritation over the reception of the sketches – a kind of reverse picture of this article in the form of a little satirical play, which was never published.21 In 1928 he wrote a lengthy obituary about Stanislaw Przybyszewski in Oslo Aftenavis22 which was also published in German in the literary journal Pologne litteraire.23 He also wrote an obituary “In memory of Jappe Nilssen” in Dagbladet24 in 1931. In 1928 Munch published a commentary regarding his relative, the painter Edvard Diriks, and his large retrospective exhibition. The commentary was printed in the catalogue and quoted both in Tidens Tegn and Dagbladet. In 1932 he published a long personal commentary in Dagbladet25 regarding the large exhibition of contemporary German art at Kunstnernes Hus that same year. The soon-to-be 70-year-old painter used very laudatory terms to describe the new German art, its pure vibrant colour and musicality, and he pointed to the many similarities it had with the presentation of new French art that had recently been shown at the same place: “One can perhaps speak of a European art now”. A German translation of the article is found in the archives of the Akademie der Künste in Berlin, but it is not known whether it was ever published in Germany.

Edvard Munch, the writer, could also present himself from a less serious side on various occasions. In 1919, in the program26 of a play at Chat Noir in Oslo, he wrote an amusing presentation of the Danish humorist, draughtsman and actor Robert Storm-Petersen, alias Storm P., who was also a remote relative of Munch’s. Storm P. was a guest performer at Chat Noir that year, and every evening, as part of the cabaret, he drew a caricature based on an actual subject! In 1928, Munch wrote down a few reminiscences from the Grand Café that were published in the anniversary publication27 of the Grand’s waiters’ union, Kruset, on the occasion of its 25th anniversary.

The Frieze of Life and The Origins of The Frieze of Life

CAT. 31. JENS THIIS 1909

Edvard Munch published two small pamphlets at his own expense that have been the subject of great interest in the research on Munch from the time they were published: The Frieze of Life from 1919 and The Origins of The Frieze of Life, most likely printed in 1929. The pamphlet The Frieze of Life was published in the wake of his exhibition of the “late Frieze of Life” at Blomqvist in October 1918. At the opening of the exhibition he published the article “The Frieze of Life” both in the catalogue and in Tidens Tegn. The article was intended as an explanatory introduction to the background and idea content of the Frieze. The exhibition received poor reviews and a few weeks later Munch attacked his critics – and Aftenposten in particular – in his article “Criticism of ‘The Frieze of Life’”. Both articles later formed the basis for the publication of the pamphlet, where he also included a couple of good and a couple of extremely poor reviews from the previous years, illustrated with motifs from the Frieze. In her dissertation, Art Historian Tina Yarborough says of the pamphlet: “Munch deliberately included positive reviews as well as several negative responses to dramatize his critical struggle in his home country. [...] A close analysis of Munch’s booklet reveals both how deeply he was offended by the criticism and how unpopular the Frieze of Life and its links to Germany had become during the war.”28 By incorporating Edouard Gérard’s essay from 1897 in the pamphlet, he attempted – according to Yarborough – to demonstrate that even the French understood his art. Munch himself writes in a note: “It has never been understood in Norway – It was in Germany that it received its greatest recognition, just as it was in Germany that my art was altogether first and most strongly understood [...] But also in Paris the frieze received much recognition – In 1897 it was given the place of honour in the main room at L’independent, furthest in. And it was this of all my art that was best understood by the French.”29 In many of his notes Munch returned to the period of the Kristiania Bohemia and its cultural upheavals as the most important motivation for The Frieze of Life and its idea content. In a letter to Ragnar Hoppe from 1929 he says: “It pleases me that You call it the ‘Scandinavian Life of the Soul’. There have been efforts to prod it down to Germany. – After all here we have Strindberg, Ibsen, Søren Kirkegaard and Hans Jæger and in Russia Dostojewski”.30 And to Jens Thiis: “You do not have to exert yourself to explain the appearance of the frieze of life – It has its origins in the period of the bohemia – It was a question of painting life as it was lived and one’s own life – In addition I already had the entire frieze of life finished long ago in the form of poetry so it was already completely planned many years before I arrived in Berlin ...”.31

In connection with the comprehensive exhibition at Blomqvist in January 1921, Verdens Gang managed to exchange a few words with Edvard Munch and Jappe Nilssen in passing: “Are you not going to publish your memoirs soon? Jappe Nilssen suddenly asks. – Don’t believe him! It’s a lie! Munch responds and then disappears in a flurry.”32 It appears, nonetheless, that during the 1920s Munch spent a lot of time going through his own journals and notes. He had turned 65 in 1928 and had enjoyed great success in Norway with the exhibition at the National Gallery the previous year, and the idea of a Munch Museum was launched from several quarters. This may have formed the background for his wish to make a mark also as a man of words – both autobiographically and as a literary man. The task of going through the journals and notes resulted in yet another booklet which he in all probability had published in 1929. This collection of notes he called The Origins of the Frieze of Life.33 The booklet contained a selection of aphorisms about art’s essence and the work of the artist; a re-writing of the journal entry from St. Cloud from 1889, the previously mentioned St. Cloud Manifesto; a lengthy entry about the 1890s, where a version of the Scream text was also included, and finally a newly written text he called “Towards the Light” in which he linked The Frieze of Life to the University Aula decorations and to the motifs related to The Human Mountain. Towards the Light.

ILL. 29. THE ORIGINS OF THE FRIEZE OF LIFE. EXHIBITION CATALOGUE. BLOMQVIST ART DEALERS 1929

It was not without a touch of vanity that Munch generally chose the aphorisms, in addition to autobiographical notes and prose poetry when he now published excerpts from his journals – thus giving himself the role both of poet and artist-philosopher. Many of the aphorisms in The Origins of the Frieze of Life have also remained famous after his death – such as this one: “The camera cannot compete with the brush and the palette – as long as it cannot be used in hell or in heaven.”

A letter to Ragnar Hoppe dated Oslo, February 1929 provides a key to Munch’s thoughts about his own journals and notes. He writes: “... as I have just recently taken a look at a number of notes which I have made in the course of over 40 years, and which are a form of spiritual journal entries. They follow in the footsteps of my paintings and engravings and could easily be included with my engravings in a complete volume. – It has also for many years been my intention to prepare a large portfolio of the most important engravings in the frieze of life and add words to it – mostly poems in prose. – [...] I have a couple of small booklets already printed, a few copies, but for the time being do not show them to anyone. – From these booklets one will be able to see that the frieze of life and my spiritual art had their origins in the bohemia period in the middle and end of the 1880–90s and that it gained a more solid form during the 1889 sojourn in Paris”.34

As an introduction to the catalogue for the exhibition at Blomqvist in March 1929 Munch printed some of the aphorisms from The Origins of the Frieze of Life in addition to a few newly written ones, dated Ekely 1929 (“1889–1929: small excerpts from my journal”). The introduction to the catalogue attracted a certain amount of attention: Dagbladet printed a short article on 14(?) March 1929: “For the exhibition at Blomqvist, which opens tomorrow, Edvard Munch has prepared a catalogue which is of particular interest since he makes his debut as a writer and makes public excerpts from a journal that celebrates its 40th anniversary this year. We have permitted ourselves to select a few phrases ...”.35 A review of the exhibition in Morgenbladet 15 March 1929 also quoted from the journal excerpts.

The work of reviewing the literary notes and the many fragmented memoirs most likely brought up scores of memories that were too exhausting and disturbing to permit a larger publication. The inscription “To be burned” that he added to several of the notebooks most likely stems from the period following this work. But only two or three years later, in 1932, Munch had changed his mind, crossed out the inscription, and wrote: “To be read by sympathetic and open-minded men after my death.” With the future, and his death, in mind – and perhaps after achieving greater peace of mind – he had decided to leave the task to his friends; the Philologist Sigurd Høst and his Doctor Kristian Schreiner.

Notes

1 Ludvig Ravensberg. Journal. LR 536. Entry: 6.1.1910.

2 Ibid.

3 The original draft from 1889, cf. MM N 289.

4 Letter from Edvard Munch to Karl Vilhelm Hammer. Private collection (eMunch.no: PN 260).

5 Cf. eMunch.no: MM UT 3. (Facsimile available for this and the following MM UT nos.)

6 “Fritz Delius” [Unsigned article. Perhaps by K.V. Hammer himself?], Verdens Gang 12.10.1891.

8 Letter from Edvard Munch to Emanuel Goldstein, 8.2.1892 (MM N 3036).

9 Letter from Edvard Munch to Emanuel Goldstein, undated (June 1892) (MM N 3039).

10 Vilhelm Krag: “Text til Edvard Munchs maleri ‘Stemning ved solnedgang’ (Katalog Nr. 8)”, Dagbladet 19.9.1892.

11 Letter from Edvard Munch to Karl Vilhelm Hammer, 16.11.1892. Private collection (eMunch.no: PN 265).

13 Thadée Natanson: “M. Edvard Munch”, La Revue Blanche, Year 6, Vol. IX, no. 59 (1895).

16 Gösta Svenæus: “Strindberg och Munch i Inferno”, Kunst og Kultur, no. 1 (1967).

17 Letter from Edvard Munch to Ludvig Ravensberg, post stamped 10.2.1905 (MM N 2828). Cf. also Sivert Thue’s article in the printed catalogue that discusses “The City of Free Love”.

18 Ibid.

20 Cf. eMunch.no: MM UT 20, MM UT 21, MM UT 25, MM UT 26.

28 Tina Yarborough: Exhibition Strategies and Wartime Politics in the Art and Career of Edvard Munch, 1914–1921, Dissertation (Doctor of philosophy), University of Chicago, 1994, pp. 362–368.

30 Letter from Edvard Munch to Ragnar Hoppe, February 1929 (MM UT 6PN 1140).

31 Draft of a letter from Edvard Munch to Jens Thiis, undated (MM N 2061).

32 “Et par ord med Munch”, Verdens Gang 18.1.1921

34 Letter from Edvard Munch to Ragnar Hoppe, February 1929 (PN 1140).

Translated from Norwegian by Francesca M. Nichols