Edvard Munch – The Narrator

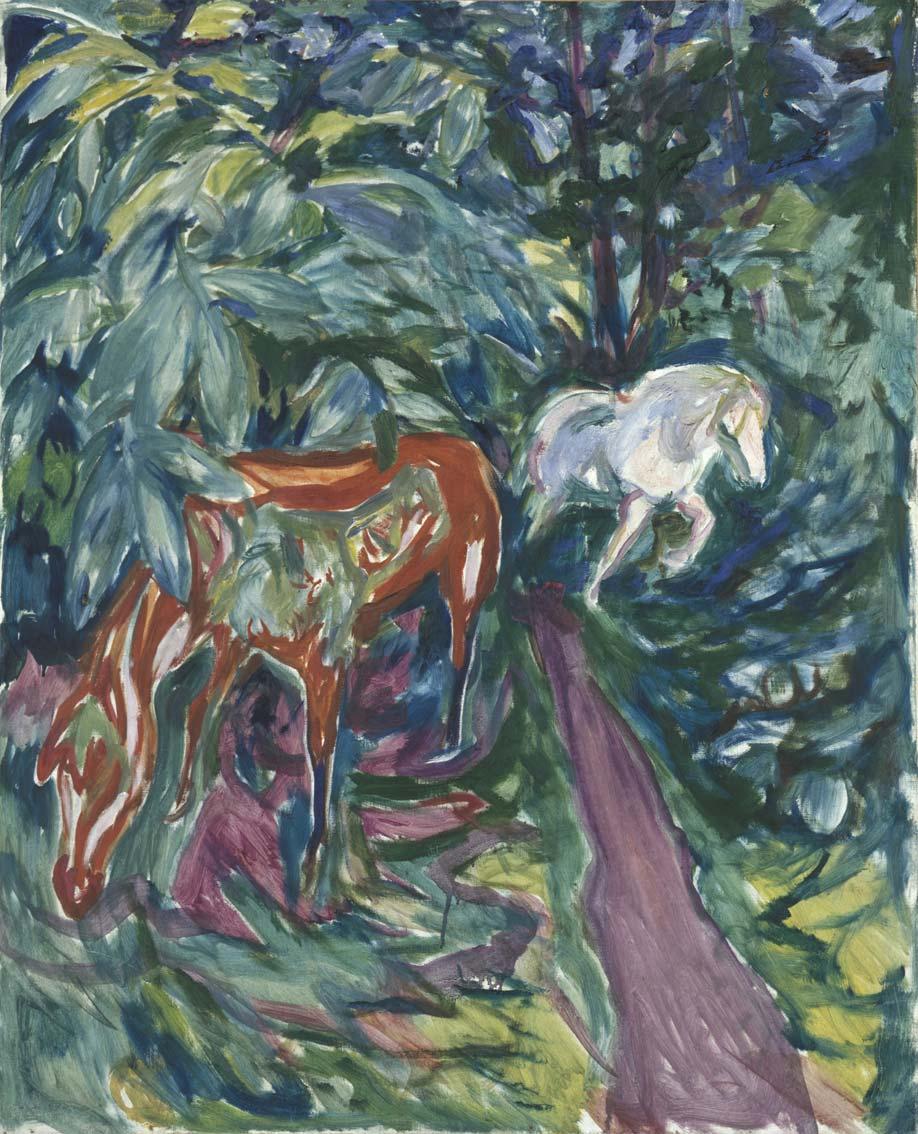

CAT. 41. TWO HORSES IN THE FOREST 1926

A striking feature of Edvard Munch’s pictures is their “literary” and narrative qualities. Well-known paintings – such as Vampire, Separation and Madonna – are figure paintings that depict humans engaged in activity. In this sense, they enter into a tradition that began during the Renaissance, where depicting people engaged in activity was considered one of the greatest tasks of art. But as opposed to figure painting’s traditional presentation, the action in Munch’s pictures is of a more open and ambiguous character. The action cannot be directly identified via specific written sources; neither his own nor the writings of others. Munch’s imagery is created in an indeterminate landscape of personal references and an almost infinite sphere of ideas and concepts, visual and literary sources.

The “literary” or “spiritual” features of Munch’s imagery was recognised by critics as early as the 1890s, and was deemed positive or negative – depending on which artistic theory the critic himself embraced. The aim of this article is not to present an analysis of the discourse on modernism surrounding Munch’s pictures. I wish instead to present some of the characteristic features of his narrative imagery. My perspective is that mental, verbal and physical pictures can be seen as related phenomena.1 The relationship has its origins in everything that occurs when pictures are created – in the form of mental images linked to memory, imagination, ideas and concepts, as well as concrete factors, such as verbal and visual expression. Munch’s narrative pictures are based on his own experiences. These experiences were not only of a personal or private character, but also consisted of culturally established literary and visual concepts.

The term “narrator” refers primarily to Munch’s role as one who uses images and texts to tell stories. The concept of “narrator” is not intended in the sense of a narrative voice in a text, but in the broad sense of one who presents stories in the form of concrete works of art.2 It is important to emphasise that “the story” – “the narrative” – does not refer to “the tale” or “the plot”, but to concrete expression in the form of pictures or text. The story’s “plot” or “story”, or understood more loosely as the “content” or “motif”, cannot be distinguished from the way it is presented – its “form”. A picture’s composition, pictorial elements, colours, cropping and brushstrokes – or a text’s narrative voice, syntax and construction – is what constitutes the story together with notions, ideas and culturally established concepts.

I will use three examples to illustrate characteristic features of Munch as a narrator. Alpha and Omega, my main example, is used to present the complex sphere of culturally established concepts and the artist’s own experiences – from romantic drama to circus shows – which together contribute to form a story in Munch’s imagination. His use of Ibsen characters form the point of reference for treating the relationship between “the motif’s” open quality and the factors that elicit recognition in the pictures’ web of references. The example of the vampire motif is chosen for a discussion of Munch’s repetitions of his motifs and the shifts in meaning that occur when he manipulates the pictorial elements.

CAT. 76. ALPHA AND OMEGA 1908–09

Alpha and Omega

The lithographic portfolio Alpha and Omega consists of a series of pictures supplemented by a story in print.3 The printed text is intended to be read alongside the pictures. In this sense, a reading of the text takes place over time and encourages a sequential perception of the individual pictures in the series. The printed text is a brief epic fable with a beginning and an end, and is about the first humans, Alpha and Omega (cat. 76). The narrator of the text presents a somewhat formal overview of the events, which he does not participate in himself:

ALPHA AND OMEGA were the first Humans

on the Island. Alpha lay in the Grass and slept

and dreamed, Omega approached him, looked at

him and became curious. Omega broke off a

Fern branch and tickled him, so he awoke.

Alpha loved Omega; they sat in the Evenings

leaning into one another and gazing at the golden

pillar of the Moon, which swayed and rocked in

the Ocean surrounding the Island.4

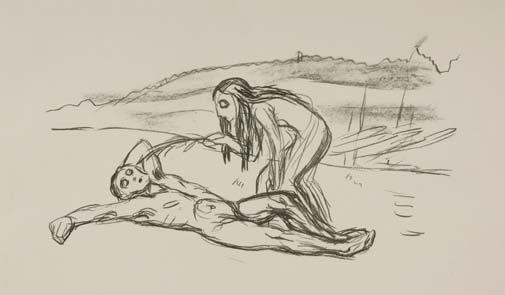

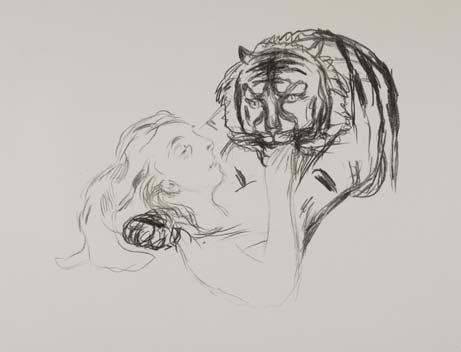

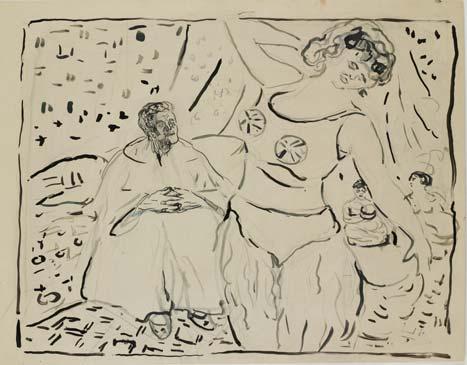

The events occur in an indeterminate primordial past on an island. The couple lives a paradiselike existence, surrounded by animals and plants. Omega becomes bored and allows herself to be seduced first by the Serpent, and then in turn by the Bear, the Poet Hyena, the Tiger (cat. 77) and the Donkey, in addition to the Pig and other animals. After a time she leaves the island on the back of a Doe and travels across the ocean to “the light green Land, that lay beneath the Moon”.5 Alpha remains on the island together with Omega’s offspring – a whole new generation of children – “little Pigs, little Serpents, little Monkeys and little Predatory animals and other Human Bastards”.6 One day Omega returns, and Alpha drowns her. He is in turn torn asunder by her small mixed offspring, who finally take over the island (ill. 67).

CAT. 77. THE TIGER 1908–09

ILL. 67. THE DEATH OF ALPHA 1908–09

Munch’s story refers to many well-known presentations and images from European cultures and traditions. Aside from the obvious reference to the Bible’s first human beings, Adam and Eve, the names Alpha and Omega are also metaphors signifying the first and the last, the beginning and the end.7 In Munch’s story Omega is the name of the woman who leads the first humans into selfdestruction because of her vanity. A similar literary version of the biblical Eve is found in John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667). It is Eve’s vanity that causes her to fall for the serpent’s guile, just as Munch’s Omega is misled by her longing to be desired. Omega’s promiscuity and her many small bastard children also recall associations to the figure of Lilith.8 According to the rabbinic writings in the Talmud, Lilith was Adam’s first wife and mother to all the demons; and in European literature and art she was depicted as a femme fatale. A Lilith appears in Goethe’s Faust (1808), and later in the century as a character in the Scottish author George MacDonald’s much-read novel Lilith, published for the first time in 1895.9 Munch may not have read any of these; however, he could have learned of the notion of Adam’s first wife and all of her demon children’s origins via his poet friends; August Strindberg, for example. He had written a fragment for a play in 1902 with the title The Dutchman.10 The main character in the play has had six unfaithful wives. The marriage with his seventh wife Lilith is at first a happy one, but it ends with her getting bored and desiring everyone but him. The play had not been published when Munch wrote his fable, but it is very likely that the unfaithful Lilith had come up in conversations between the two friends around a café table in Berlin or Paris.

Munch also used models and events from his own life when he created Alpha and Omega. He had amused himself among other ways by imbuing the animal figures with “portraits” of his “dear foes”, as he wrote to Gustav Schiefler.11 Schiefler passed on this explanation of the connection between Munch’s own life experiences, and the series of pictures, in an article he published in a German art magazine.12 Those whom Munch referred to as “foes” were his ex-fiancé Mathilde (“Tulla”) Larsen and her supposed lover Gunnar Heiberg, together with their “helpers”, men such as Sigurd Bødtker and Christian Krohg. This image of foes had its background in a concrete episode in 1902. Munch felt that he was being pursued by Tulla Larsen, whom he had promised to marry; but he was now trying to extricate himself from their relationship against her will. During a confrontation between the two of them, Munch was distractedly fiddling with a pistol that went off by accident and injured his left hand. After this, he constructed a complex web of enemies that developed into paranoid delusions, and grew in magnitude in keeping with his increasing use of alcohol. In the fall of 1908, as we know, he was admitted to Dr. Jacobson’s clinic at Frederiksberg in Copenhagen for detoxification, and it was during his stay there, 1908–09, that he created Alpha and Omega.13

The gallery of figures in Alpha and Omega is formed on the basis of literary references as well as on actual people in Munch’s life, but the scenario with all of the animals is independent of both. A whole gallery of animals appears here as acting participants in a human drama – as Omega’s lovers. Munch must have been familiar with H.C. Andersen’s fables, in which animals or inanimate things are imbued with human characteristics. Perhaps he had also read Jean de La Fontaine’s fables in the popular 19th century edition illustrated by Gustave Doré. As opposed to Munch’s case, the animals participate in the plot of these fables with dialogue and they are also depicted with a greater number of human attributes. In Munch, most of the animals appear first and foremost with their conventional characteristics – the serpent creeps, the bear is brawny and furry, and the tiger is ferocious and wild.14 Their most prevalent human attribute is that they have allowed themselves to be tamed by Omega’s female charms. Women who have sexual intercourse with animal figures has been a common motif in art since antiquity. Jupiter, Neptune and other ancient gods disguised as various animal figures – serpents, swans, dolphins and oxen, to name a few – seduce scores of women.15 Munch’s animal combinations, however, distinguish themselves from the classical fables as well as from the mythological world of the gods. In Aesop and La Fontaine we find toads, rats, foxes, bears and other animals that come from European fauna, in addition to those known from ancient Mediterranean cultures, such as lions and turtles.16 In Alpha and Omega’s world, the group of animals is combined in a totally different way.

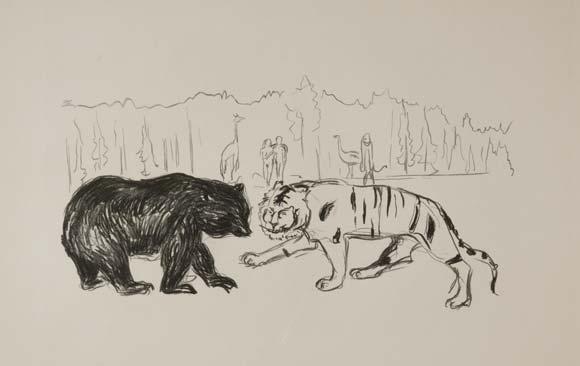

CAT. 78. THE TIGER AND THE BEAR 1908–09

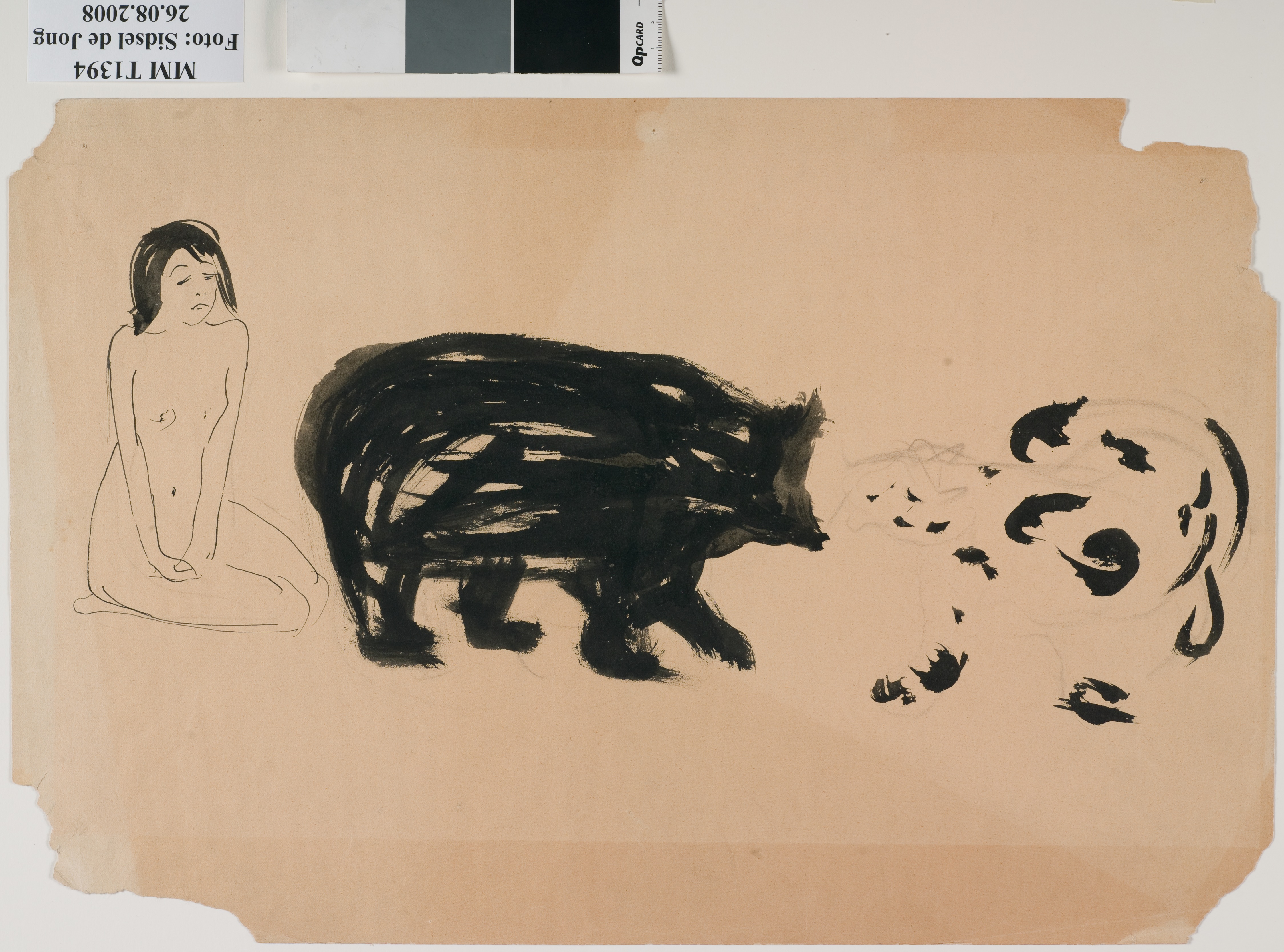

On Alpha and Omega’s island there are many animals that are not known in European nature. In addition – and this is more important – animals from diverse habitats occur together. Both in the texts and in some of the lithographs, hyenas, tigers, bears, ostriches, dogs, does and pigs appear side by side. There is also a unique confrontation here; two predatory animals – the tiger and the bear – stand face to face (cat. 78). With a little good will, one might imagine that this confrontation had its origins in Munch’s frequent visits to the zoo in Copenhagen during his work on Alpha and Omega. However, there is a similar situation in the drawn sketches for the story The First Human Beings (c 1895). In one of the drawings a sketch of a woman, bear and tiger can be seen (ill. 68). Here the anatomy and appearance of the animals is far more sketchily described than in the lithograph. The regular and deliberate visits to the zoo during his stay at Dr. Jacobson’s clinic provided an excellent opportunity to study animals in motion.17 But the special combination of animals that appear together, also in the drawing from c 1895, gives us reason to assume that he got the idea from having seen a comparable situation.

Munch did not have Animal Planet or Discovery Channel to watch in order to become familiar with an exotic animal universe. He did have access to travelling circuses and zoos, however, where he could experience the most unbelievable shows with trained beasts of prey.18 It was previously common to show tigers and lions locked up in cages, but towards the end of the 1860s, the animal trainer, circus director and zookeeper, Carl Hagenbeck, developed an animal training program that was based on reward instead of punishment.19 This made it possible to develop performances with combinations of animals, which from the standpoint of nature are enemies. Hagenbeck and his pupil Richard Sawade, for example, had an extensive travelling enterprise with animal troupes of this type. In the shows, one could see animal pyramids with polar bears on top, then Asian White-chested bears, tigers, and lions, and on the bottom, dogs that were trained to jump over the backs of the predators (ill. 69 and ill. 70).20

ILL. 68. THE WOMAN, THE TIGER AND THE BEAR C 1895

I 1889 Hagenbeck was at the World Fair in Paris with his mixed animal troupe, and in 1896 at the industrial exhibition in Berlin.21 Munch can very well have seen the show in Paris, because he visited at least one other event during the World Fair – “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show”. In a letter home to his aunt Karen Bjølstad he wrote enthusiastically about Buffalo Bill’s fight with the Native American chief, and the scalp and knife that could be viewed in the hero’s tent. He also mentioned that there had not yet been enough time to visit the historical sites of the city, because the exhibition took all his time.22 Events such as “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show” and Hagenbeck’s travelling circus were well-reputed entertainment shows and had both kings and emperors as guests of honour.23 The performances gathered thousands – up to 100,000 spectators in two weeks – and, when it comes to audiences and general interest, can be compared to today’s blockbusters at the cinema.

ILL. 69. GROUP OF ANIMALS TRAINED BY RICHARD SAWADE C 1900

ILL. 70. POSTER SHOWING RICHARD SAWADE AND HIS GROUP OF MIXED ANIMALS C 1902

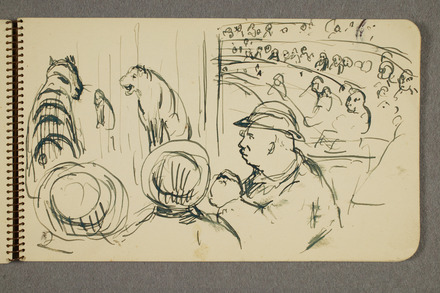

ILL. 71. CIRCUS PERFORMANCE, FROM SKETCHBOOK MM T 288-13 1929

But Munch also had abundant opportunities to see animal performances in his daily life. During the long periods when he lived in Berlin, from 1893 to 1908, he often took walks in the large public park, Thiergarten, situated next to the Berlin Zoo. In the summer of 1907, Munch also had the opportunity to visit the zoo in Stellingen on the northern outskirts of Hamburg. The inauguration of the zoo on 7th May 1907 caused newspaper headlines all the way across the Atlantic, for the animals were for the first time separated from the public with moats instead of iron bars. Hagenbeck was photographed in the newspapers walking in the midst of large groups of tigers and lions, while lovingly patting the predators on the head.24 One could also observe African ostriches walking about in the open air. In the summer and winter of 1907, Munch stayed primarily in Warnemünde, but was in Hamburg several times in order to visit Gustav Schiefler and other friends. That summer he showed Schiefler the old drawings of “the first human beings” – with the tiger and the bear.25 If Munch visited the zoo in Stellingen, it could have influenced his decision to visit the zoo in Copenhagen in 1908. When Circus Hagenbeck visited Kristiania (Oslo) in 1916 he was a frequent guest, a fact that is revealed in the diary of his relative Ludvig Ravensberg.26 On this occasion Munch made a portrait of the circus director Richard Sawade together with one of his tigers.27 The circus revisited Oslo in 1929, and Munch made a sketch seen from the gallery (ill. 71).28

The Garden of Eden connotations form a visual and thematic kinship between Munch’s series of pictures and the circuses. In the circuses the tamed predatory animals were placed together with what in nature would have been their prey. Hyenas, lions and tigers performed together with horses, goats and lambs.29 “The Lion and the Lamb” rested peacefully side by side in a paradise-like state.30 The cultivating of the animals was reminiscent of their peaceful coexistence with the first humans before the fall of man. The dramatisation of the zoos as a modern Eden was underscored not only by the combination of the animals, but also in the use of painted landscape panoramas. In 1898 in Berlin, for instance, a semi-circular panorama was mounted with painted backdrops and groups of “paradise” animals: “Carl Hagenbeck’s zoological paradise: the zoo of the future”. The animals were taken from the trained troupes of the circus. The public could gain access from inside the zoo or directly from the train station which was adjacent to it.31 The diorama was not aimed at providing information about the animals’ link to the habitat, but at underscoring the harmonious relationship between animals, which in nature would have been enemies.32 The idea of a modern Eden is therefore not only linked to a phenomenon of a visual and physical character, but to a world view that provided a framework for seeing the zoo in a specific perspective.

In other words, Munch made use of a wealth of resources when he created the story about Alpha and Omega. But instead of claiming that he was inspired by this or that, or that Omega “is” Lilith, Eve or Tulla Larsen, one could say that everything he experienced and assimilated in his memory became the raw material of his imagination and the story. Munch did not use one story as the foundation of his narrative, but many. All of the known material – all of the references to concepts, literature, iconography – are there resonating beneath his own narrative.33

Instead of focusing on all of Munch’s “sources”, we can turn our gaze towards the viewer and the reader. The “sources” live on in the viewer as well, in a chain of associations, which Munch’s narrative has set in motion. A similar strategy underlies his use of narratives and figures from Henrik Ibsen’s literary world. Munch made more than 400 paintings, drawings and graphic works based on Ibsen’s plays, which interested him because he found a fundamental affinity between his own and Ibsen’s way of seeing the world.34 It is just as important to point out that in Ibsen’s plays and gallery of characters; he found a source to give his own narratives identity and credibility.

Munch, Ibsen and Fiction

The title The Death of Marat (cat. 26) refers to the French revolutionary Jean-Paul Marat’s death at the hand of Charlotte Corday. The painting was exhibited for the first time at the Salon des Indépendants in Paris in 1908 with the title La Mort de Marat, which it subsequently retained.35 There are no explicit sources that reveal why Munch chose this title, but it is reasonable to assume that it was to give the French public a familiar story they could relate the painting to. For a Norwegian or German public familiar with Henrik Ibsen’s play, the motif could also be reminiscent of the dramatic events in Hedda Gabler. In the play Hedda Gabler gives her old flame Ejlert Løvborg one of her two identical pistols, and challenges him to take his own life in a “grand way”. One shot from the pistol kills him, though not with the heroic “grandiosity” that Hedda Gabler had wished. Løvborg dies from a shot to his groin in the red-haired Miss Diana’s boudoir – that is, in the room of a prostitute. The chain of events around the shooting is unclear – how the shot was fired, who fired it, whether it was an accident or whether the “able-bodied young girl” Miss Diana has killed him.36 The ice-cold and calculating Hedda Gabler is also an accomplice to Løvborg’s death. In one of Munch‘s drawings (cat. 56) she is depicted standing alone in the second before she takes her own life, dressed in black and by the curtain that is a central stage element in the play. Her disappointment over Løvborg’s wretched demise results in her taking her own life “in a grand way”: through the temple. In Munch’s figure, her rigid, frontal position mirrors the figure in the naked red-haired girl in The Death of Marat, thus creating a hidden kinship between the two women.

CAT. 26. THE DEATH OF MARAT 1907

Munch painted The Death of Marat and similar paintings, such as the The Murderess (cat. 27), at the same time that he was making the stage scenery for Hedda Gabler for Max Reinhardt’s theatre in Berlin, which opened in February 1907. For a visual artist who from as far back as the 1890s had been preoccupied with creating fiction out of his own life, it is no wonder that Munch found episodic similarities between his own experiences and literature. Only five years earlier, in 1902, he had lived through the dramatic shooting incident with his own red-haired woman, Tulla Larsen.37 In his book Kunsten, kvinnen og en ladd revolver. Edvard Munch Anno 1900, Frank Høifødt has shown how the chain of events in the shooting incident – who did the shooting and how – gradually changed in the course of the following years.38 Munch himself contributed in covering up the chain of events surrounding the shooting incident in 1902, just as it was also unclear how the shot was triggered in Hedda Gabler.39

CAT. 56. HEDDA GABLER 1907

CAT. 27. THE MURDERESS 1907

One can claim that the assertion that Munch used Ibsen to fictionalise his own life necessarily makes his experiences less “true”, and that it can therefore be claimed that the events did not take place. I would argue the very opposite, that this was how Munch explains the events in his personal life crisis – in order to create narratives that others can also grasp. All storytelling – whether it is fictive or non-fictive – is construed and shaped.40 This does not imply anything more than that the narrative about what has occurred is developed with the help of ideas and concepts, and given concrete expression. The fictive narrative can even have a special function as a “stamp of truth”. How this occurs in Munch’s case can be illustrated with an example from a totally different quarter – from the courtroom in a case from 1893, taken from Richard Walsch’s book The Rhetoric of Ficitionality. Narrative Theory and the Idea of Fiction.41 In a trial against a young woman who was charged (but later acquitted) with having killed her father and step-mother, the prosecution and the defence evoked rhetorical credibility in their presentation of the chain of events by comparing them to well-known “master plots” from literature and culture – narratives with authority and credibility. The accused young woman’s apparent lack of emotions in light of the murders was explained by the defence as the result of the virtuous daughter’s shock at the events. The prosecution, on the other hand, explained it by comparing her with the cold-blooded Lady Macbeth. These two culturally established narratives were used to add an aura of truth to their presentation of the chain of events surrounding the murders. The participants attempted to create narrative credibility by comparing their representation of the events to rhetorically relevant “master plots”.42 Munch made use of “master plots” in a similar way to fictionalise incidences from his own life. In this way the narratives gained rhetorical weight. The same effect is achieved when Munch weaves other Ibsen themes into his own well-known motifs, such as Ashes, which is re-constructed as a Peer Gynt motif (cat. 70). It is interesting to note that he often gave his Ibsen figures his own facial features (cat. 68). By re-using motifs and elements from his own compositions, they simultaneously gained new and doubled significance. resentation of the events to rhetorically relevant

CAT. 70. ASHES (PEER GYNT) 1930s

CAT. 68. PEER GYNT. ANITRA DANCING. PEER WATCHING (ACT 4) C 1930

The question is therefore not whether the “plot” or the “motif” in The Death of Marat “is” Marat and Charlotte Corday, Munch and Tulla Larsen, or Ejlert Løvborg and Miss Diana or Hedda Gabler, respectively. Munch has not painted the couple as an iconographic riddle to be solved. It is painted ambiguously because it is the object of the viewer’s experience, perception and reflection. Its open quality appeals to the viewer’s own ability to envision pictures. The pictures are thus created in the viewing over time, and do not appear only as presentations of a detail of an “incident” or a “story”. The narratives are not created in the artist’s mind, isolated from a communicative, social sphere. They are also created in the viewing or reading of them by the viewer or the reader.

Repetition and a Gradual Shifting of Meaning

The open character of the pictures is also illustrated by Munch’s practice of repeating motifs. Instead of claiming that he sought in this way to retrieve the first impression of an experience, I would claim that by these repetitions he demonstrated that the “action” in the pictures was not fixed. This becomes clear when one studies Munch’s repetitions of the Vampire motif side by side. As Per Faxneld shows in his article in the printed catalogue, it is reasonable to consider the historical and cultural implications of how Munch’s vampire motifs were understood. Munch’s original title for the picture from 1893 was Liebe und Schmerz (Love and Pain), but he was quick to accept the title Vampire, suggested by his friend, the Polish writer Stanislaw Przybyszewski.43 Munch thereby also accepted the accompanying, culturally established concept of the blood-sucking woman.44 He later asserted that the motif was really a woman kissing a man on the neck, and among the papers he left behind are a number of written drafts of such a scene. These can possibly be dated to the early 1890s. Here is a description of the intense feeling a kiss on the neck arouses in a man:

He lay his head against

her chest – he heard

the beating of her heart – felt the blood

rushing through her veins – and he

felt two burning lips

against his neck – it

sent a shiver

through his body – a freezing

desire so that he convulsively

pressed her to him45

Many of the same elements are found in another written draft:

He studied her brooch

that shone with red lights –

he felt it with

his trembling fingers

And he leaned his head against

her chest – he felt the blood pulsing

in her veins – he listened to the

beating of her heart – He buried his face in her lap

(She bore her

head down on him – and) he felt

two burning lips against his

neck – it sent a shiver

through his body – a freezing desire

– So that he convulsively

pressed her to him.46

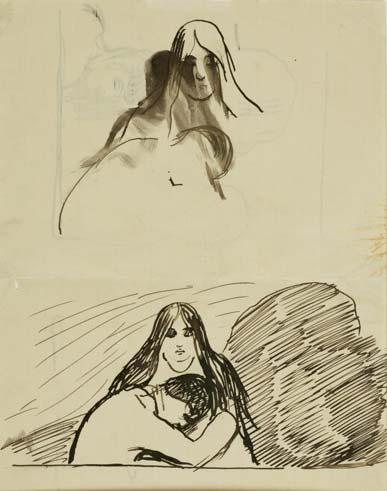

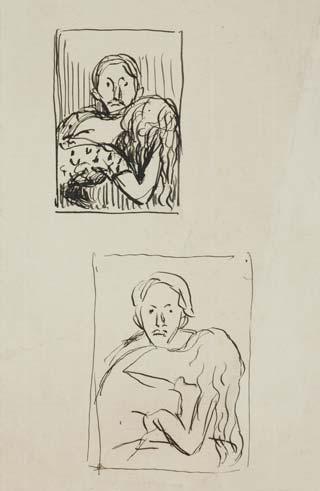

CAT. 49. TWO SKETCHES FOR VAMPIRE 1892–93

CAT. 69. VAMPIRE (CONSOLATION) 1930s?

The early drawing Consolation (Vampire) from 1886–90 (cat. 44, p. 279), can also be seen in light of Munch’s “narrative” about the burning kiss on the neck.

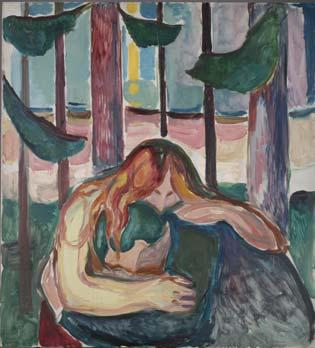

CAT. 36. VAMPIRE 1916–18

CAT. 34. VAMPIRE 1916–18

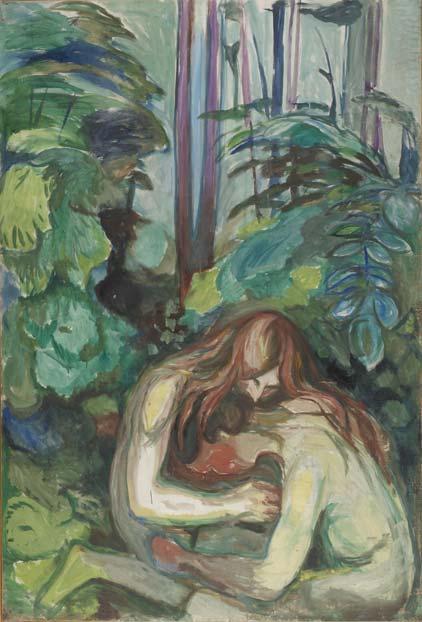

This does not mean, however, that the motif is “really” of a woman kissing a man on the neck. Munch used an experience to create an image that awakens interest and recognition in the viewer on many levels. Yet, the open and ambiguous quality of the picture does not arise only in relationship to the viewer, but also in Munch himself. This is demonstrated in his playing with the subject by shifting the pictorial elements. For example, the drawing Two sketches for Vampire (cat. 49) has a visual counterpart in Vampire (Consolation) (cat. 69), which shows a man kissing a woman in the neck – or perhaps it is a male bloodsucker? Munch painted several pictures of the vampire motif during the 1890s, such as cat. 11, p. 196, and cat.17, p. 186, and took it up again in several paintings during the years 1916–18. The dominating shadow in cat. 17 can be seen in a spectrum of purple and green in two paintings from 1916–18 (cat. 34 and cat. 36). These were most likely not intended for exhibition or sale, but were a means of exploring how experimentation with the formal elements affected the subject matter of a picture.47 The vampire paintings are not simply additional pictures that refer to the same story; each painting consists of a story in itself. The colours and lines of the pictures, and how the brushstrokes cover the canvas – all these are elements in the stories about a kiss or bite on the neck by a woman or a vampire, respectively, or perhaps both.

CAT. 35. VAMPIRE 1916–18

ILL. 72. VAMPIRE IN THE FOREST 1916–18

ILL. 73. KISS ON THE SHORE BY MOONLIGHT 1914

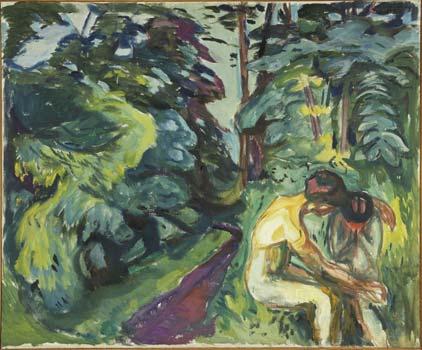

When Munch exhibited his Frieze of Life at Blomqvist Art Dealers in 1918, he chose to include the painting he called “Woman Kissing a Man on the Neck”, known today as Vampire in the Forest (ill. 72). A similar composition is found in cat. 35. The couple has been moved outdoors and placed against a nature background that can be recognised from other paintings by Munch, for example Summer Night. The Voice (cat. 19, p. 153). The shoreline in the background, the line of trees, the narrow cropping and the reflected pillar of the moon are used as pictorial elements in conjunction with another Munch motif – the vampire. He has done the same in several other paintings – such as in Kiss on the Shore by Moonlight (ill. 73) and Vampire in the Forest (ill. 74). During the 1920s Munch created a series of pictures of a naked couple in a forest. The man bending over the neck of a woman is found in Consolation in the Forest (cat. 37). The naked couple and the beautiful horses (cat. 41, p. 218) in the verdant forest are once again reminiscent of the Garden of Eden, the first human beings Adam and Eve, or Munch’s own human couple – Alpha and Omega.

Munch’s repetitions of the same motif are thus not merely that all of them are associated with the same action, in the sense of a sequence of events that can be retold. It is rather that each individual picture is a narrative, and it arises only in an encounter with the viewer. The subject matter – such as a vampire, a kiss or consolation – is moved about from one Munch scenario to another – thus creating new relationships between his paintings. The elements and motifs of the pictures are transformed into a visual language where the parts are interchangeable. Pictures are woven into pictures, story into story. This hidden connection between the pictures can be seen in different ways. One can claim that Munch is citing or referring to his own pictures, or one can say that he has constructed a visual language in which the forest’s vertical tree trunks, the shoreline and reflected pillar of the moon form the signs in a language construct. When placed in conjunction with other signs – such as “vampire” – new narratives are created. A similar working method drove Munch to make a great number of written drafts that encompass the same motifs or figures. In this catalogue we have printed one of his written texts in which the literary figure “Mrs Heiberg” appears (pp. 239– 274),48 yet among his papers there are approx. 45 documents of varying length in which she also appears.49 Some of the drafts are quite similar in that they contain many of the same plot elements. At other times, he has cut and re-arranged elements of a chain of events and put them together in new ways.

ILL. 74. VAMPIRE IN THE FOREST 1924–25

CAT. 37. CONSOLATION IN THE FOREST 1924–25

Munch’s imagery is “literary” in several ways; that is, if by this one means that it draws references from literature, ideas, concepts and other culturally established narratives. With their strong presence, the pictures impose something of significance, yet their visual openness forces the viewer to become active – to attempt to understand, to reflect and to seek insight. The ambiguity that Munch has imbued the pictures with via his painting method, appeals to the viewer’s involvement in a more powerful way than dogmatic art could ever manage to do. Instead of providing clear answers, the pictures’ ambiguity challenges the viewer’s imagination and ability to envision pictures. The pictures’ visual rhetoric is meant to activate the viewer and stimulate reflection, emotions and awe. This means that Munch’s pictures are never emptied of meaning and that we will never become tired of exploring his complex and rich universe of images.

Notes

1 See the introduction to this catalogue. This concept of images is taken from W.J.T. Mitchell: Iconology. Image, Text, Ideology (1986).

2 For further information regarding the narrative as concrete expression in the form of an artwork or written text, see for example Mieke Bal: Narratology. Introduction to the Theory of Narrative. Third revised edition 2009 (first publ. 1985). Toronto: University of Toronto Press Inc., pp. 3–14.

3 Edvard Munch: Alpha and Omega, lithographic portfolio 1908–09. The portfolio contains one sheet of text in Norwegian and French printed in regular book print, plus lithographs of the title sheet, table of contents, two vignettes and 18 large pictures. Gerd Woll: “The Alpha og Omega Portfolio”, in Edvard Munch : Alpha & Omega (exhibition cat. Munch Museum 25 March – 3 May 1981), pp. 8–10. The texts may have been written after the pictures were made.

4 Alpha and Omega is available for viewing in facsimile and as a transcript at eMunch.no: MM UT 32.

5 Ibid.

6 Op.cit.

7 The first and last letters of the Greek alphabet are used in the Bible to signify Christ: “I am Alpha and Omega, the first and the last, the beginning and the end”. The Book of Revelation 22,13. Regarding Munch’s references to Adam and Eve, see Frank Høifødt: Kunsten, kvinnen og en ladd revolver. Edvard Munch Anno 1900, Forlaget Press, Oslo 2010, pp. 35–55.

8 Gerd Woll: “Alpha og Omega. Munch’s Pictoral Fable of the First Two Human Beings”, in Edvard Munch and Denmark (Exhibition cat.), Ordrupgaard/Munch Museum 2009/2010, pp. 38–45.

9 Wild animals, serpents, tigers and leopards appear in this book as well. It is not known if Munch has read the book. It is generally only in rare cases that one can with reasonable certainty ascertain whether he has read a book. He was very good at covering his traces. During the registering of Munch’s writings (2007–10) his library from Ekely was gone through with the idea of finding notes or marks in the margins of the books. Only a very few such traces of reading were found. Even in cases where the pages of a book have not been cut open, one can only deduce that he did not read this particular copy. Theoretically, he could have read another copy or a previous edition that he had borrowed or owned and later lost.

10 August Strindberg: “Hollenderen”. Otryckta skrifter. Otryckta dramatiska arbeter. Stockholm: Bonniers Förlag 1918, pp. 202–54.

11 Letter from Munch to Gustav Schiefler, 13.4.1909. Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Hamburg. Available for viewing at eMunch.no: PN522.

12 Gustav Schiefler: “Edvard Munchs Alfa og Omega”. Kunst und Künstler, 1910, No. 8, pp. 409–413.

13 Arne Eggum gives credence to the nervous breakdown and the break with Tulla Larsen in 1902 in his article “Alpha og Omega. Edvard Munch’s Satirical Love Poem”, in Edvard Munch : Alpha & Omega (Exhibition cat. Munch Museum 25 March – 3 May 1981), pp. 39–54.

14 “The Poet Hyena” is an exception. He is a shabby fellow, and falls for her tribute in the form of a laurel wreath. In Western culture the hyena has since antiquity been seen as an animal with a strong sexual identity. It was also considered to be a sexual hybrid or hermaphrodite because the male and female genitals are nearly identical. This perception is found in Ovid’s Metamorphosis and in the medieval bestiaries (animal fables having a moral content), where hyenas were also associated with the devil.

15 The motifs in these images are taken from by the Roman author Ovid’s Metamorphosis.

16 The serpent, tiger and bear also appear in Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book from 1894.

17 Helge Rode was Munch’s regular companion at the zoo. Munch has produced 46 lithographs of exotic animal motifs. 19 of them are definitively based on drawings made at the zoo in Copenhagen, cf. Per Hovdenakk: «Nordmænd i Zoo», in Johannes Larsen Kerteminde (ed.): Museet: Dyrebar i Københavns Zoologiske Have og Kunstnere, 2002, pp. 157–58.

18 Carl Hagenbeck: Beasts and Men. Being Carl Hagenbeck’s Experiences for Half a Century Among Wild Animals, Longmans, Green & Co., London & New York 1912, p. 140. The Norwegian edition was published in 1911: Dyr og mennesker : oplevelser og erfaringer / af Carl Hagenbeck ; translated by W. Dreyer, Copenhagen ; Kristiania : Gyldendalske boghandel 1911. Beginning in the 1870s, Hagenbeck went on tour with heterogeneous groups of animals.

19 Hagenbeck, op.cit. p. 140.

20 Hagenbeck, op.cit. p. 130 ff. It was difficult enough to keep the animals from attacking each other, but even more difficult to train them to understand how to perform in specific routines.

21 Hagenbeck, op.cit. p. 135.

22 Letter from Munch to Karen Bjølstad, November 1889, MM N 722, Munch Museum. In the letter Munch calls Buffalo Bill ‘Bilbao Bill’, but the identity is unmistakable based on the details Munch mentions in the letter. Buffalo Bill’s real name was William F. Cody.

23 During the opening performance of Buffalo Bill’s show in Munich, King Ludvig II himself was guest of honour. Eric Ames: Carl Hagenbeck’s Empire of Entertainments, University of Washington Press, Seattle and London 2008, p. 110. Emperor Wilhelm II visited Hagenbeck’s zoo in Stellingen in 1907. Hagenbeck, op.cit. p. 45.

24 For the date of the opening, see: Edward P. Alexander: Museum Masters: Their Museums and their Influence. London: Sage Publications Ltd. 1995, p. 323. Photographs of this sort are found in Hagenbeck, op.cit. pp. 127 and 137.

25 According to a note in Schiefler’s diary 5th August 1907, quoted in: Arne Eggum (ed.): Edvard Munch / Gustav Schiefler. Briefwechsel, Munch Museum / Verein für Hamburgische Geschichte, Oslo / Hamburg 1987–90, p. 251.

26 Ravensberg writes in his diary that he has met Munch on the following evenings at the circus, where they were drawing. Ludvig Ravensberg’s diary, LR 558, 28.11.1916. Thanks to Inger Engan who brought this reference to my attention.

27 The portrait of Sawade: The Tiger Tamer Sawade, MM G 393, 1916. Munch’s arrangement of Sawade and the tiger is reminiscent of the lithograph Omega and the Tiger (cat. 77), or the reverse. He could have had the idea to draw Omega in this way, through previously having observed the intimate relationship between the animal tamer and the dangerous predators. There is also an unused postcard in the Munch Museum showing a photograph of Sawade and his tiger.

28 MM T 228-13v, Munch Museum. Judging from the other drawings in the same sketchbook, the book most likely stems from the 1920s. The drawing of the circus performance can be from 1929, when Hagenbeck revisited Oslo. Thanks to Lasse Jacobsen who brought the drawing to my attention. Regarding Hagenbeck’s visit to Oslo, see Herman Berthelsen: Sirkus i Norge. Gjøglernes og sirkusenes historie, Commentium Forlag, Sandnes 2009, pp. 258–261.

29 Hagenbeck, op.cit. p. 143.

30 Hagenbeck, op.cit. p. 143.

31 Ames, op.cit. p. 160 f. The backdrop was painted by Moritz Lehmann.

32 Ames, op.cit. p 161.

33 Munch’s own imagery also shows up as an inter-textual reference: it is found in Alpha’s figure and the landscape along the shore when he is struck by angst, as a paraphrase of the Scream motif.

34 Joan Templeton: Munch’s Ibsen. A Painter’s Visions of a Playwright. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press; Seattle: University of Washington Press 2008, p. xix and p. xxii.

35 Gerd Woll: Edvard Munch. Collected Paintings, Vols. I-IV, Thames and Hudson, London 2009, no. 768. Woll points out that Munch used models for the painting. Templeton believes that Munch chose the title The Death of Marat in order to distance the motif from an autobiographical framework for interpretation, Templeton, ibid. p. 61.

36 Joan Templeton links the female figure in the painting more closely to Hedda Gabler, and does not mention Miss Diana. However, the red hair and the setting of the scene provide good reason to see her as Miss Diana as well.

37 Templeton, op.cit. pp. 59–64.

38 Høifødt, op.cit. pp. 215–225. See also Sivert Thue’s article in the printed catalogue.

39 Frank Høifødt has demonstrated that Munch made it very clear early on that the firing of the shot was an accident, and that it was he who held the pistol. See Høifødt, op.cit. pp. 215–225.

40 Regarding the artificial nature of narratives, see Richard Walsch: The Rhetoric of Ficitionality. Narrative Theory and the Idea of Fiction. Columbus: The Ohio State University Press 2007, p. 14.

41 Walsch, ibid, pp. 13–14, who has taken the example from H. Porter Abbott’s Cambridge Introduction to Narrative.

42 Walsch, op.cit., p. 14.

43 Przybyszewski, Stanislaw. In Przybyszewski, Stanislaw; Servaes, Franz; Pastor, Willy; Meier-Graefe, Julius: Das Werk des Edvard Munch. Vier Beiträge, 1894, p. 20. The version of Vampire that was exhibited in Berlin was the one that is owned by the Gothenburg Museum of Art today. Woll, Gerd 2009: Edvard Munch. Collected Paintings, Vols I-IV, no. 334.

44 See also Mai Britt Guleng: “Edvard Munch and the Hidden Depths of Memory”, in Michael Fuhr (ed.): Edvard Munch and the Uncanny. Exhibition cat., Leopold Museum Private Foundation 16.10.2009–18.01.2010. Vienna 2009, pp. 22–29 and pp. 277–280.

45 MM N 618, Munch Museum, also reproduced on p. 278 in the printed catalogue.

46 MM T 2771-19r, Munch Museum. The original has a great number of corrections which are omitted here.

47 Of a total of 12 known paintings of vampire motifs from Munch’s hand, he owned eight at his death.

49 These are available for viewing at eMunch.no by searching for “fru Heiberg” or by reading the comment on “fru Heiberg” and following the links in the comment.

Translated from Norwegian by Francesca M. Nichols