“... this chaos of letters I have collected ...”1

Edvard Munch, the Letter Writer

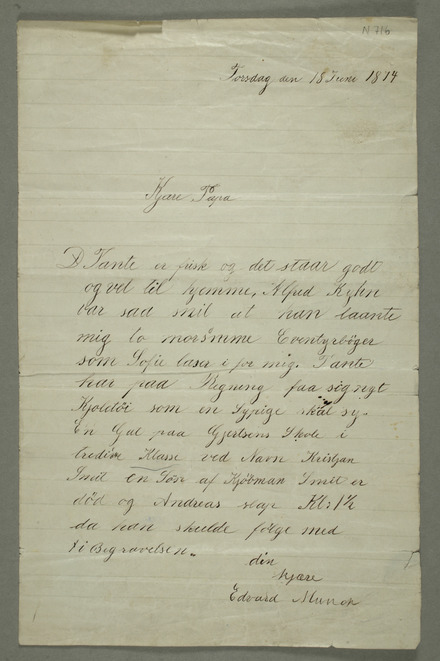

“Dear Papa”. Thus begins the first known and preserved letter from Edvard Munch’s hand. It is dated 18 June 1874. “Papa”, Christian Munch (1817–89), was working at the time as a medical doctor at the military camp at Gardermoen (ill. 13). In an even and neat cursive lettering, 10 year old Edvard writes to tell him of the great and small news of the family at home in Kristiania. The style of this letter is “childish” in the sense that it is a purely descriptive text without comments or reflections about the events being recounted.

ILL. 13. LETTER FROM EDVARD MUNCH TO HIS FATHER CHRISTIAN MUNCH 18 JUNE 1874, MM N 716

Auntie is well and everything is just fine at home, Alfred Kyhn was so kind that he lent me two fun Fairytale books that Sofie reads to me from. Auntie has gotten new Dress material on Account which the Sewing Seamstress will sew. A Boy at Gjertsen’s School in the third Grade by the Name of Kristjan Smit a Son of the Shopkeeper Smit is dead and Andreas was let free at 1:30 so that he could attend the Funeral.

your beloved

Edvard Munch2

The family letters can be said to represent a scarlet thread in Munch’s correspondence. And despite periods of conflict, he kept in touch with his family by letter throughout his life. Approximately 1000 letters and drafts of letters to his close family are registered in the Munch Museum’s database, which represents around one fourth of the total collection of letters. With time Munch gained a large circle of friends, acquaintances and business associates at home and abroad. Around 400 recipients divided by approx. 2600 letters and 1500 drafts of letters are registered as of today’s date. A good portion of these are now stored in the Munch Museum.

Munch’s Collection of Letters

Munch most often preserved his papers and documents, and a considerable quantity of letters received by him, newspaper clippings, and his own drafts of letters and notes were amassed in his home at Ekely. Munch collected them, but he did not keep them in any order or sort them, and in a sense Ekely became one great archive – as well as a studio, of course. Many of Munch’s friends have commented on the chaos and mess that eventually took hold there: Paintings, sketches, drawings and letters were everywhere. Or as Rolf Stenersen described it: “On tables and chairs lay painting supplies, brushes, canvases and tubes of paint. On the grand piano were a pile of letters and prints, and in the basement and the attic were prints, hands presses, copper plates and lithograph stones. The house at Ekely was really one huge mess.”3

When Munch was going through his papers during the Second World War, prompted by the thought of a possible evacuation, he expresses his frustration to his friend Christian Gierløff:

Well it is difficult for others to have any conception of what I have been faced with – Paintings etchings and countless letters and notes throughout 60 years – For I never used a waste basket – Instead it was my Suitcases – That is why it is so frightfully difficult to separate the wheat from the chaff but that is also why I have kept so much4

And there really was a chaos of papers that confronted Munch’s heirs at Ekely after his death. In his will Munch had made a distinction between letters and literary works. And while the literary works went to the City of Oslo, the letters were given to his sister Inger Munch – the only remaining member of Munch’s immediate family. Inger later donated the collection of letters to the City and the planned Munch Museum.5

The Letter as Communication – and Source

The letter is a manifold genre. The definition “a relatively short message from a sender to an absent recipient” encompasses, among other things, letters to the editors of newspapers, letters that are used as devices in literary texts and the wholly private message from one person to another.6 The private letter gained overwhelming popularity during the second half of the 19th century. Increased writing skills, increased mobility, Romanticism’s self-awareness and the need to express it, together with improved post roads and less costly postage, were some of the factors underlying this development.7 In other words, Munch grew up in a letter writing culture – and in a letter-writing family.

As a reader of letters we usually automatically expect the letter to be true and authentic and that we can gain true and genuine knowledge about the author of the letter through reading it. It is partially against this backdrop that many of our famous writers have had their private letters collected and published. The letters have been looked upon as a key to, or frame of reference for, the literary works.8 When it comes to visual artists, their correspondence has not had the same public interest or appeal in a Norwegian context. The exception here is Munch, who has had parts of his correspondence published on several occasions.9

Do we get a true picture of Edvard Munch by reading the letters he wrote? According to the Danish literary scholar Lotte Thrane, letter-writing is a dialogistical process in which the letter writer has a dialogue both with him/herself and with the recipient. There are thus several persons present in an exchange of letters: the two actual persons and the perceptions they have of one another, and in addition, the letter-writer’s inner dialogue where he/she chooses the theme, style, word, etc.10 This can be illustrated with the following quote in which Munch apologises for a delayed reply: “I have not written – as the whole time that I have been ill and in the most despicable humour I have not wished to risk revealing myself in a letter in such a mood –”.11 In other words, Munch wished to spare the recipient what he perceives as his real self.

When it comes to letter writing in Munch’s time, it must be added that the addressor did not necessarily only have one recipient in mind. It was often the case that a letter could be read out loud within an enclosed circle or circulated among the family and a circle of friends, even though it was addressed to an individual recipient. In addition, persons in certain public positions were often aware that their personal correspondence was worth being preserved and read posthumously. We can therefore assume that Munch at least in part had groups more than individual persons in mind when he wrote.

Letter writing is in fact not a stream of consciousness, but a more or less conscious orchestration of oneself and the other person – just as we orchestrate ourselves in a face to face encounter with other persons. We play roles all the time and adjust what we say according to whom we are speaking and based on the situation we find ourselves in.12 Through body language and tone of voice, we validate our words – or convey mixed messages. In a letter the handwriting, type of paper, writing tool and print all take on the function of this wordless communication, which reveals something about the author’s message and state of mind. Munch pointed to this aspect of letter writing in a draft of a letter to his friend Eva Mudocci:

Man kann in ein Brief nur theilweisz sich geben – in den verschiedensten Stimmungen – so viel wie moglich – diesen zeigen von verschiedenen Richtungen an der müstischen Centrum – “Ich” was vielleicht man selbst nicht kennt –13

(One can only partially reveal oneself in a Letter – in the various Moods – as much as possible – these point from different Directions to the mysterious Centre – the “Self” that one perhaps doesn’t even know oneself –)

Instead of searching for an authentic Munch between the lines, it might therefore be more productive to look at how Munch represents himself. Which roles does he take on? Which moods does he expose in his letters?

We will take a look at some examples where he addresses his family, friends, lovers and business associates respectively. These groups of recipients must not be seen as fixed, nor can all of Munch’s letters be placed in one of these categories. And neither must one believe that Munch reserves certain subjects for specific correspondents. Subjects having to do with Munch’s business transactions, and his role as artist in particular – exhibitions, sales, private finances – involve more than business associates. Both his Aunt Karen and his lover Tulla Larsen, for instance, played the role of Munch’s private bank at times and friends such as Jappe Nilssen and Jens Thiis organised exhibitions for him. The reverse can be said of clients such as Max Linde and Gustav Schiefler, who became good friends. On the whole, his role as artist forms the foundation for a major part of Munch’s correspondence. It is very rare that a letter from Munch – unless it is a thank-you card or some such brief greeting – does not have to do with his work on one level or another.

Family Letters

Much has been written about Munch’s relationship with his family – for better or worse. What is certain is that his family was extremely important to Munch, and through a multitude of letters we can glean a picture of this relationship and how Munch chose to present himself to his closest family.

He is usually tactful and solicitous in his family letters, at times by giving the stories a humoristic touch and thereby taking the sting out of what might be shocking events. When in the summer of 1902 he ends up in a scuffle with the painter Johannes von Ditten in Åsgårdstrand, a story that gained a good deal of public attention, it is revealing how he plays it down in the letter to his Aunt Karen:

I would have written before about the Incident here had I not known that You had read about it in the Newspaper and seen that the whole thing ended quite satisfactorily – Ditten received a Couple of Blows and he does not even dare to take out a Lawsuit – As for the rest by the way it was an enormous Comedy –14

In matters of money he can be almost manipulative and he unresevedly exploits his family’s goodwill in order to be able to realise his artistic ambitions. “– I paint a bit – it does not amount to much because no money arrives –”, he writes from Nice in 1891.15 Not a word about his frequent trips to the casinos in Monte Carlo ...

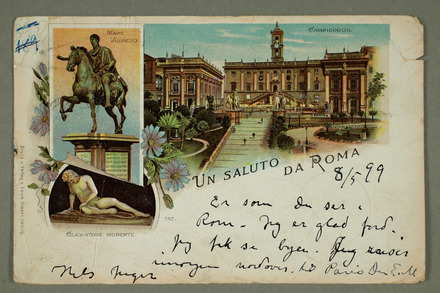

Among the family letters there are also a great number of very short messages. These are notes informing them about his whereabouts and perhaps where he is headed, and they can also be congratulatory notes, Christmas wishes and thank-you cards. In May 1899 Munch sends a beautifully colored postcard home from Rome, for instance. The card he chose was meant for extremely short messages, for on the back there was only space for the address.

ILL. 14. POSTCARD FROM EDVARD MUNCH TO HIS AUNT KAREN BJØLSTAD 1899, MM N 830

Am as You can see in Rome – I am happy that I got to see the city – I travel north to Paris tomorrow

Your E. M

Say hello to Inger16

“Merry Christmas to You and Inger/Your Edv Munch” Munch writes on a postcard to his Aunt Karen in 1920.17 The handwriting is large, hasty and totally without punctuation. The postcard’s motif, Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson’s grave, is probably also more a sign of his hectic schedule than it is a deliberately chosen Christmas motif on Munch’s part.

These terse letters can be viewed as impersonal and dutiful family correspondence and as an expression of thoughtful consideration and a sense of belonging. Munch had a strained relationship with his family at times, especially with his sister Inger, which resulted in his avoiding personal encounters with her. At the same time it is obvious that he felt attached to his family – for many years he was also financially dependent on them – and via brief and long letters he maintained contact with them. Behind the seemingly impersonal words and the hurried handwriting we can glimpse a caring nephew and brother.

Love Letters

Tulla Larsen and Eva Mudocci were two significant women in Munch’s life, who left their mark on his paintings and writings. Munch’s original letters to these two have been lost, but a number of drafts have been preserved, as have a few later transcriptions of Munch’s posted letters to Mudocci.18 Munch’s relationships with these two women were in many ways fundamentally different – not least in the significance they had after the fact. In Munch’s own life, the relationship with Larsen became the root of most of his later problems, while his relationship with Mudocci evolved instead into a sweet memory. Yet if we look at how Munch construes himself in writing in his encounters with these women, we can also find similarities. It is an eager and smitten Munch who writes to Larsen:

Perhaps a drive to Holmenkollen – or somewhere else – Can we meet at a restaurant here in town? Perhaps You could come up to my place today or tomorrow? – then we can make an appointment –19

Far more poetically, yet just as eagerly, he writes to Mudocci a few years later:

Ich wunschte Du warst hier – Ich wollte Dich vor mich halten – Deine beide Armen Hande in meinen und Deine beide Augen in meine – so wollte ich mit Dir sprechen –20

(I wish that You were here – I would hold You in front of me – both Your Hands in mine and both Your Eyes in mine – in this way I would speak with You –)

Munch’s way of subsequently attempting to extricate himself from the love affairs is characteristic. To Larsen he repeatedly points to the distance between them, which makes a relationship impossible unless they are able to establish a brother-sister relationship. She belongs to this earth and to life, while he stands outside or above this world: “– and You will continuously seek an earthly happiness with me, who as I always explained to You does not belong to this earth –”.21

During the time we have been together – in all of the moments – when we lay close to each other – when we viewed the magnificent wonders of Florence – when we walked together along a sunlit road – when we sat together – and even in the moments that should have been the most intensely happy – even then happiness shone on me merely as through a door ajar – a door that divided my dark cell from the brightly lit ballroom of life itself –22

By appealing both to Larsen’s reason and to her feelings, he attempts to extricate himself from his connection with her, and it is at times an unsympathetic Munch who shows up in these drafts of letters. It almost seems as though he wishes to present himself as so unattractive that she will cease wanting him. He is both mean and condescending when – after having offered to marry her pro forma – he takes on the role of being her artistic and intellectual mentor: “You could make etchings – and I would buy books for You – and You could educate Your Spirit which is not developed in the least”.23

ILL. 15. MEETING IN SPACE 1925–29

The drafts of letters to Mudocci are on the whole extremely poetic; everything that had to do with her and their relationship in particular inspired a metaphorical and grandiloquent language in him. Through this language he places them and their relationship in a higher sphere; it is a spiritual relationship Munch establishes in the drafts to her. “Ich glaube unsere Seelen offnen sich für einander” (I believe our Souls open themselves up to one another).24 “Du bist Musikk” (You are Music).25 “Ein mal werde ich mein kranke Seele in Dein Musik mir baden – es wird mich wohl thun” (One day I will bathe my ailing Soul in Your Music – it will do me good).26 Even misunderstandings and quarrels become draped in a conciliatory veil when Munch compares them to “Schneegewitter fur die Fruhlingsblumen” (a Snowstorm for Spring Flowers).27 “Spring Flowers” here is a metaphor for the two of them and their relationship.

Munch renders these love affairs impossible by elevating them to a platonic level; they are not of this world, but are rather encounters that take place in space. The position at Munch’s side was in addition already occupied, as he writes in a draft to Larsen: “[Art] is my great love”.28

Letters to Friends

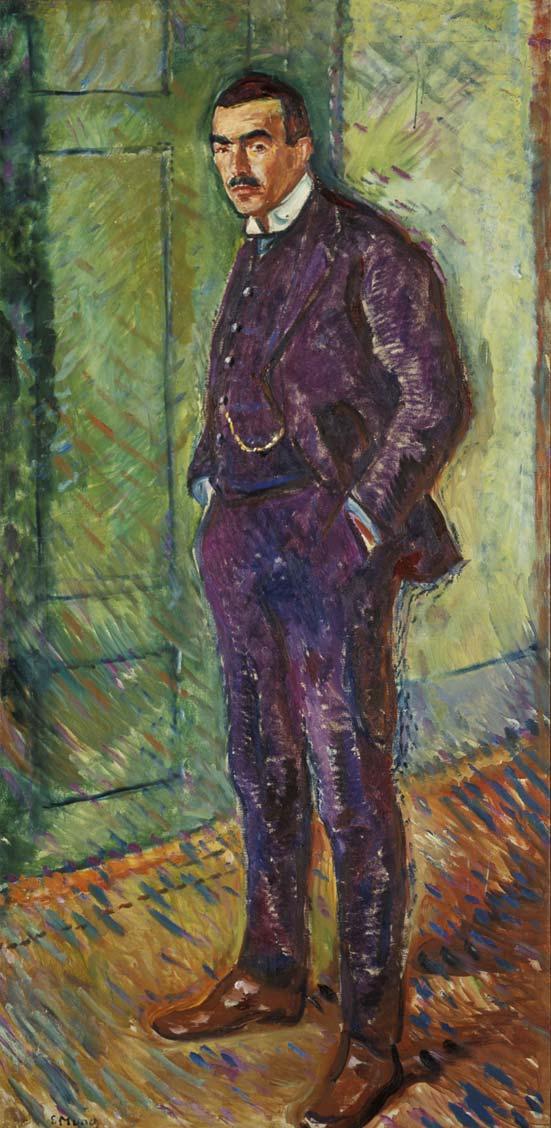

CAT. 29. JAPPE NILSSEN 1909

“And I am aware that I have more Friends than I had believed”, writes Munch to Jappe Nilssen in 1908 – as he momentarily peers over his imagined list of enemies which he had built up throughout many years of physical and psychological overexertion.29 True enough. Munch had a large circle of acquaintances, and close and more distant friends. Among those considered to be his most intimate friends throughout many years were Ludvig Ravensberg, Jappe Nilssen, Jens Thiis, Sigurd Høst, Harald and Aase Nørregaard and Christian Gierløff. Munch writes lengthy and very personal letters to some of them – and he involves them deeply in his work. They do errands for him, assist him with exhibitions and mediate in the selling of his works. It is also in the letters to friends that Munch reveals the most extreme sides of himself, both the dark and the light. It is to friends that he most ruthlessly exposes his inner life; and his sense of humour also reveals itself through peculiar observations, irony and a few illustrated drawings.

Some of the most intimate and undisguised letters to friends stem from the time Munch spent at Dr. Jacobson’s Clinic in Copenhagen, which lasted from October 1908 to May 1909. Here he underwent detoxification treatment and was assisted in learning how to organise his days according to fixed and healthy habits. In a letter to Sigurd Høst he describes his new self:

I have entered the Order “Do not touch anything”: Nicotine-free Cigars – alcohol-free Drinks – Poison-free Women (neither unmarried nor married) – So you will find me a very boring Uncle indeed –30

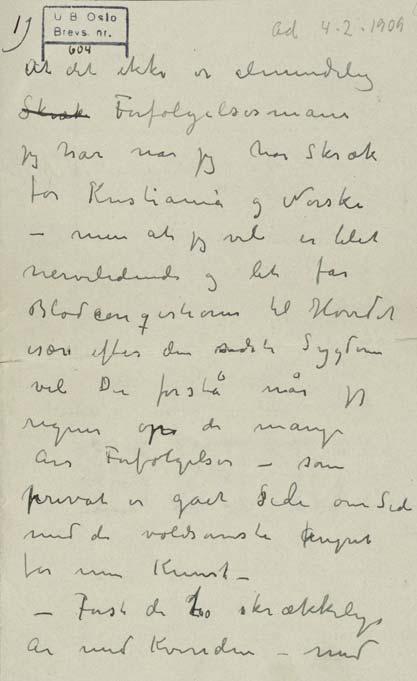

Some of the correspondence from his stay at the clinic can almost be characterised as therapeutic writing. For example there are a number of letters to Jappe Nilssen from these months, where he again and again goes through everything that he believes has made him ill (ill. 16).

That it is not common Paranoia that ails me when I have a Fear of Kristiania and Norwegians – but rather that I have a nervous condition and easily get Blood congestions in the Head especially after my last Illness You will understand when I make a list of the many years of Persecution – which in my private life has occurred Side by Side with the most violent Attacks on my Art –31

CAT. 22. AASE NØRREGAARD 1902

He then enters into an account of the hardships associated with the enemy, who, among others, includes Tulla Larsen, Christian Krohg, Knut Hamsun, Andreas Haukland, Johannes von Ditten (the incident with Ditten is not such an “enormous Comedy” here as it was in the letter to his Aunt Karen), the media in general and Aftenposten in particular. And then, after a 13 to 14-page harangue about this, his business affairs:

To speak of another matter: I would in fact like to sell as cheaply as possible to the Gallery [The National Gallery] – but I don’t believe the Gallery will lose out in buying from me – after all the Prices are constantly rising –32

The handwriting is typical of Munch at that time: hasty, a little slapdash and with the widespread use of the dash as punctuation mark. This gives the letter a spontaneous and almost impressionistic quality, where both the content and the form become personalised.33

ILL. 16. LETTER FROM EDVARD MUNCH TO JAPPE NILSSEN 1909

Business Letters

Business letters are not often the most exciting or savoury part of a person’s correspondence. But they can be interesting just the same, both as a major source of information about the culture they were penned in and about the comings and goings of the author of the letter. Munch’s many letters to gallery owners, buyers, printers and public offices give us a broad picture of the enormous enterprise Edvard Munch represented during his lifetime.34 Beyond that they demonstrate that Munch was polite, sophisticated and could express himself according to the conventions of the time. This is the case, by the way, as long as everything is going well. The moment the gallery owner interprets an agreement differently than Munch, the moment the shipping agency doesn’t do its job or Munch believes the tax authorities are making outrageous demands on him, his temperament makes itself known also in the business letters.

In 1902 a shipping agency muddles a shipment of some of Munch’s works. He is out of the country at this point in time, so he puts Harald and Aase Nørregaard on the case to find out what has happened. When the items finally show up Munch writes an extremely sarcastic letter to Schie’s Transport Company.

Your Letter arrived!

In that Connection the following Comments – First and foremost I will of course no longer leave it to You to Transport my Things (If You sent my Things to a Boer in South Africa, would I then also have to pay for the Two-way shipment?) We are – it appears in agreement that the public should be Informed of – in all its Details – how a Norwegian Shipping agency conducts it Work and causes a Painter directly and indirectly large Monetary losses. – I feel it is my Duty to see that this Case with all its Details is made public – [...] If my missing Woodcuts should be found among those arrived from Åsgaardstrand – it would also prove the accidental nature of the Previously arrived ruined Painting – how You were pleased to disperse my Works across God’s fair Earth – [...]

Very Respectfully

Yours Edv. Munch35

The closing salutation, which would normally seem appropriate according to the conventions of the time, become in this context profoundly ironic.

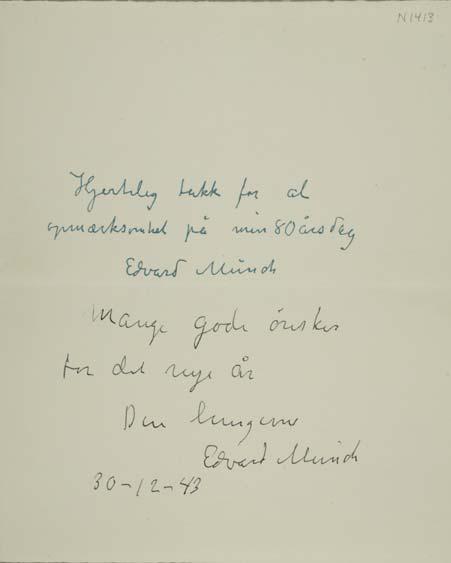

The Last Letter

On 12 December 1943 Munch turned 80, and on that occasion he received numerous greetings from well-wishers in Norway as well as abroad. Afterwards he made the job of writing thank-you notes more efficient by printing multiple copies of a letter with the following text:

A heartfelt thank-you for all of the

attention I received on my 80th birthday

Edvard Munch

Three of these thank-you notes are known, all of them signed 30 December 1943; they are addressed to Inger Munch, Harald Hansen and Halfdan Roede.36 To each of them Munch added an extra greeting and signed them once more with his name and the date. To his sister he politely wrote (ill. 17):

ILL. 17. LETTER FROM EDVARD MUNCH TO HIS SISTER INGER MUNCH 30.12.1943, MM N 1413-1

Many good wishes

for the new year

Your devoted

Edvard Munch

30-12-43

Three weeks later Edvard Munch passed away, alone at Ekely.

The abundant collection of letters which Munch left behind has become a vital source of information about his life and work. Munch was aware that the letter was an orchestration of oneself – a linguistic presentation of one’s “various moods” as he wrote in the draft of the letter to Eva Mudocci. He chose which of these moods he wished to display to the various persons that he corresponded with. In this way Munch’s extensive correspondence can function as a gateway to his “mysterious Centre – the ‘Self’”.

Notes

1 Draft of a letter, Edvard Munch to Harald Nørregaard, undated, MM N 1958, Munch Museum.

2 Letter, Edvard Munch to Christian Munch, 18.06.1874, MM N 716, Munch Museum. The reproductions of Munch’s original texts follow the rules of diplomatics as far as possible. This implies for example that misspellings are not corrected, while missing punctuation is inserted when required for legibility. In the Norwegian texts the dot over the “i”, the circle of the “å” etc. are inserted even when Munch did not include them. In the German texts, missing accent marks over “ö” and “ä” etc. are not inserted. Regarding Munch’s Norwegian and German, cf. Hilde Bøe’s and Christian Janss’s articles.

3 Rolf Stenersen, 1969, Edvard Munch : Close-Up of A Genius:115.

4 Letter, Edvard Munch to Christian Gierløff, 1943, MM N 3027, Munch Museum.

5 During this process Inger went through the papers, and the question has been raised whether she discarded some of the material. Cf. also Lasse Jacobsen’s article “Edvard Munch’s Writings after 1944 – Fragments of a Research and Publication Chronicle”.

6 For a concise review of the letter writing genre cf. John Chr. Jørgensen, 2005, Om breve : Ni essays om brevformen i hverdagen, litteraturen og journalistikken:10 ff.

7 Kerstin Dahlbäck, 1994, Ändå tycks allt vara osagt : August Strindberg som brevskrivare: 22–23.

8 Narve Fulsås, 2005, “Introduction” to Henrik Ibsens skrifter 12 : Innledninger og kommentarer : Brev 1844–1871:25. In addition letters by a writer can of course have value as literature in their own right. August Strindberg for example considered his production of letters as an integral part of his writings, cf. Dahlbäck: 293–94.

9 Cf. Lasse Jacobsen’s article “Edvard Munch’s Writings after 1944 – Fragments of a Research and Publication Chronicle”.

10 Lotte Thrane, 1999, Længselsbilleder : En beretning om forførelse, skrift og passion: 36.

11 Draft of a letter, Edvard Munch to Tulla Larsen, 1899, MM N 1823, Munch Museum.

12 Fulsås: 23–24.

13 Draft of a letter, Edvard Munch to Eva Mudocci, undated, MM N 2380, Munch Museum.

14 Letter, Edvard Munch to Karen Bjølstad, 17.08.1902, MM N 850, Munch Museum.

15 Letter, Edvard Munch to Karen Bjølstad, 1891, MM N 765, Munch Museum.

16 Letter, Edvard Munch to Karen Bjølstad, 08.05.1899, MM N 830, Munch Museum. In the original we can see a period after “nordover” [“north”] and that Munch has added “to Paris Your E. M”.

17 Letter, Edvard Munch to Karen Bjølstad, 23.12.1920, MM N 990, Munch Museum.

18 Waldemar Stabell supplied the story behind Munch’s letter to Eva Mudocci, which possibly still exists, cf. “Edvard Munch og Eva Mudocci” in Kunst og Kultur 1973. We know that Munch’s letters to Tulla Larsen were burned after her death, cf. Jens Dedichen, 1981, Tulla Larsen og Edvard Munch: 75.

19 Draft of a letter, Edvard Munch to Tulla Larsen, 1898–99, MM N 1805, Munch Museum.

20 Draft of a letter, Edvard Munch to Eva Mudocci, undated, MM N 2367, Munch Museum.

21 Draft of a letter, Edvard Munch to Tulla Larsen, 1899, MM N 1826, Munch Museum.

22 Draft of a letter, Edvard Munch to Tulla Larsen, 25.05.1899, MM N 1813, Munch Museum.

23 Draft of a letter, Edvard Munch to Tulla Larsen, 1899, MM N 1833, Munch Museum.

24 Draft of a letter, Edvard Munch to Eva Mudocci, undated, MM N 2367, Munch Museum.

25 Draft of a letter, Edvard Munch to Eva Mudocci, undated, MM N 2381, Munch Museum.

26 Draft of a letter, Edvard Munch to Eva Mudocci, undated, MM N 2382, Munch Museum.

27 Draft of a letter, Edvard Munch to Eva Mudocci, undated, MM N 2372, Munch Museum.

28 Draft of a letter, Edvard Munch to Tulla Larsen, 1900, MM N 1865, Munch Museum.

29 Letter, Edvard Munch to Jappe Nilssen, 17.10.1908, Collection of Correspondence 604, The Manuscript Archive, The National Library of Norway.

30 Letter, Edvard Munch to Sigurd Høst, 31.03.1909, MM N 3257, Munch Museum.

31 Letter, Edvard Munch to Jappe Nilssen, 04.02.1909, Collection of Correspondence 604, The Manuscript Archive, The National Library of Norway.

32 Ibid.

33 Strindberg also developed a “dash technique” at the beginning of the 1870s, but unlike Munch, Strindberg later abandoned the practice, cf. Dahlbäck:119. In his biography Stenersen has a lengthy and almost poetic interpretation of Munch’s handwriting: 149.

35 Letter, Edvard Munch to Schie’s Transport Company, 1902, MM N 2025, Munch Museum.

36 Letter, Edvard Munch to Inger Munch, 30.12.1944, MM N 1413, Munch Museum. Letter, Edvard Munch to Harald Hansen, 30.12.1943, private collection. Letter, Edvard Munch to Halfdan Roede, 30.12.1943, private collection.

Translated from Norwegian by Francesca M. Nichols